The history of female prostitution in Australia

By Raelene Frances,

From W.I.S.E. Women's Issues and Social Empowerment, 1994

Synopsis

When local councillors and other prominent citizens planned appropriate ways to celebrate the 1993 Kalgoorlie Centenary, a group of Hay Street sex workers suggested a brothel museum as a fitting tribute to the longstanding contribution of the prostitution industry to the town's economic and social life. While the city aldermen were not quite ready for such an idea, its conception raises a number of issues about the history of prostitution in Australia. Most obviously, the sex workers were drawing attention to the hypocrisy of the official disapproval of their industry alongside the open toleration, even encouragement, of the Hay Street brothels as a facility for local men and as a tourist attraction for the town. Equally important is the idea of prostitution as a subject for historical investigation and representation. What kinds of objects and texts could be included in such a museum?

Introduction

The changing physical environment of prostitution is an obvious starting point. One scene might depict the interior of an 1890s hessian tent (through which enterprising policemen could poke spyholes in their quest for conclusive evidence of commercial sex), equipped with a wooden box on top of which washbowls contain water costing almost as much as a 'short-time' with the tent's occupant. Next to the basin, a handful of metal tokens struck with the silhouette of a young woman on one side and a name and address on the other. The only other furniture is an iron bedstead, above which is pinned a medical certificate signed by the local doctor proclaiming the prostitute (a young French woman) free of venereal diseases. Draped across the end of the bed, a collection of lacy underwear, silk stockings, high-buttoned boots and brightly coloured clothing. Moving forward in time, the next scene might contain an interior of a weatherboard and iron house, 1920s. Cleanly but basically furnished, it has a basin with cold running water in the corner. Through the door a bathroom, with chip heater, is visible. On the dressing table lies an Italian newspaper left behind by the last client. The final scene shows a street view of the same room in the 1970s, framed by a car window. The top half of the door opens independently of the bottom (in the manner of a horse stabledoor) to reveal a scantily clad woman sitting inside, lit by coloured lights. In the background the watchful eye of an older woman, expensively dressed and bejewelled, surveys the prostitute and the onlooker.

Such a display, while potentially very evocative and illuminating about the changing working conditions and even to some extent the working relationships of goldfields sex workers, nevertheless could not elucidate the more complex issues associated with the changing nature of prostitution over time. It would require considerable amounts of text to explain the complex range of factors which shaped, and still shape, the sex industry: changing economic options for women; changing sexual practices and values within the prostitute and non-prostitute community; technological changes; developments in medical treatment; shifts in the general economic climate; wars; racial ideologies; and, probably most importantly, changing state interventions in the form of legislation and its administration by the police, courts, prisons and other government agencies. This chapter will explore this complex history and the way in which it has been dealt with by Australian historians. It will look exclusively at female prostitution, since male prostitution is virtually absent from the historical record and entirely absent from the historiography.

Prostitution in Pre-Colonial Australia

It is a conventional wisdom that prostitution is the oldest profession and that it has existed in all societies in all times. The case of Aboriginal society before the European invasion refutes the latter claim. As far as we know, prostitution, in the sense of the exchange of sexual services for goods or money, did not exist in traditional Aboriginal society. Most (but not all) Aboriginal societies did practise some form of polygamy, but this was not prostitution. Nor was the ritual exchange of women as a sign of friendship between different groups of people (Williams and Jolly, 1992, pp.9-19). The earliest hints we have of commercialised sex are with the Macassar fishermen who visited the northern shores of Australia on a seasonal basis from at least the 1670s. There were certainly sexual liaisons between these fishermen and local women, and cases of Aboriginal women returning to Macassar with their lovers. There is also evidence of a barter system whereby Aboriginal people exchanged local goods for rice, calico, alcohol and fishing equipment. Oral histories record some cases of women being exchanged for dugout canoes but it is unclear how widespread this was, or indeed whether it was in the period before European contact or in the later period (the trade did not end until 1907) when Aboriginal societies and economies were under greater pressure (McKnight, 1976).

Prostitution in the Convict Era

Historians are on firmer ground when talking about prostitution in the post-invasion period, although our knowledge is by no means complete here either. As feminist historians have shown, prostitution was an integral part of the social and economic system of the early convict colonies. The numerical predominance of males on the first convict ships (amongst both convicts and gaolers) was from the outset perceived as a social and political problem: those in authority believed that 'without a sufficient proportion of that sex [female] it is well known that it would be impossible to preserve the settlement from gross irregularities and disorders' (Martin 1978, pp.22-9). Women were needed as an antidote to sexual deviance (read sodomy), rape of 'respectable' (read upper class) women, and rebellion. It was thus a matter of considerable urgency to find female sexual partners for the European colonists. Aboriginal women were obvious candidates for this role, and indeed Arthur Phillip, the first Governor, hoped that in time Aboriginal men would 'permit their Women to Marry and Live' with the convicts (Rutter, 1937). In the short term, however, this was not practicable and, as subsequent events were to show, liaisons between convict men and Aboriginal women were to cause much interracial tension (Reynolds, 1982). Having toyed with and rejected (on humanitarian grounds) the idea of luring Polynesian women to Sydney, the authorities turned to the possibility of bringing in significant numbers of women convicts. The issue here was not miscegenation, as it was to become by the end of the nineteenth century. Class considerations were paramount. The favourable response later on to Japanese prostitutes was based not just on their quietude but also on the fact that they didn't appear to have half-caste babies very often.

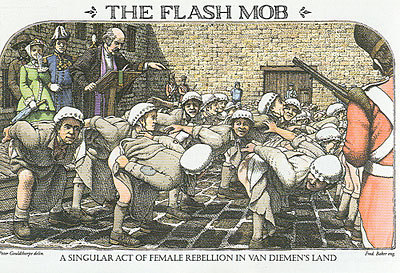

The plan was only partly successful. Only one quarter of the convicts transported on the First Fleet were women. If we add gaolers and officials to the numbers of males, women were outnumbered by roughly six to one in the convict settlements until the increase in free female immigration in the 1830s (Carmichael, 1992, p.103). To achieve even this level of comparability in the numbers of men and women, the authorities had to transport women on much less serious offences than those for which men were transported (Robson, 1963, 1965; Oxley 1988). But, the supply of female offenders was still not sufficient to keep pace with that of male convicts. This meant that, if the intention to use these women as sexual partners for convicts was to be fulfilled, some or all of the convict women would have to have multiple male partners. Indeed, in Phillip's opinion, 'the lusts of the men were so urgent as to require the prostitution of the most abandoned women to contain them' (Rutter, 1937). The fact that 12 percent of convict women were recorded as prostitutes before leaving Britain no doubt predisposed them to continue their former occupation in the colony (Robson, 1963). Other conditions in the penal settlements encouraged widespread prostitution. In the early years of the settlement no provision was made for housing for female convicts and a woman's best chance of accommodation was through striking up a liaison with some man. Those who could not or would not attach themselves to one man found the temporary bartering of sex for accommodation just as effective. Women were also the frequent targets of male violence and many found it necessary to seek the protection of one man, in return for sexual favours, against the sexual demands of other men. Limited opportunities for female employment in the early years, where the major demand was for male muscle-power, also placed pressure on women to prostitute themselves as one of the few ways in which they could earn a livelihood. According to Anne Summers, the result was a situation of 'enforced whoredom', either to one man or to many (Summers 1975, pp.267- 85; see also Alford, 1984, p.44; Aveling, 1992).

There is considerable debate about the exact level of prostitution in convict society (Lake 1988). Historians such as Lloyd Robson (1965), Alan Shaw (1966) and more recently Robert Hughes (1987) have tended to accept the judgements of contemporary officials who condemned the female convicts generally as 'damned whores', possessed of neither 'Virtue nor Honesty'. But the evidence upon which this judgement is based is problematic. How can we know, for instance, whether the frequent allegations of universal whoredom reflected the class- and sex-based prejudices and preconceptions of literate officials more than actual practices in the colony? As Michael Sturma has pointed out, middle and upper class commentators tended to see working class women as prostitutes simply because their behaviour transgressed their own class-based notions of feminine modesty and morality. For instance, long-term de facto relationships were a common and accepted part of early nineteenth century working class culture, but from the perspective of the middle or upper class observer, these women were prostituting themselves, albeit to 'one man only' (Sturma 1978). Such men were also shocked by working class women's open and aggressive sexuality compared to that of 'virtuous' women of their own class (Daniels 1993). Early feminist historians such as Anne Summers and Miriam Dixson have ironically reinforced this picture of wholesale whoredom by incorporating the stereotype as a key element in explaining Australian women's current low status in relation to Australian men. Women were compelled into prostitution by State policy and structural factors rather than their own personal 'vice' but they were, by these accounts, prostitutes nonetheless (Summers 1975; Dixson 1975). Portia Robinson (1985), writing in the mid-1980s, presents the opposite view of the women of Botany Bay as good wives, good mothers and good citizens. If they were prostitutes, she says, it was as a result of their criminal environment in Britain rather than conditions in Australia. On the contrary, Australia offered women the chance for redemption (Robinson, 1988, p.236).

In the final analysis, it is impossible to know exactly how many women engaged in commercial sex during the convict period. Despite this, prostitution obviously was a key institution in convict society, providing one of the few economic options for women who supplied a high level of demand for sexual services in a disproportionately male population (Alford 1984). There is a sense, too, in which the actual numbers of women working as prostitutes is irrelevant to an understanding of the place prostitution played in colonial society. What is more important is the fact that those in authority believed it to be widespread yet, apart from ritual expressions of disgust, showed a high degree of toleration for the practice. As noted earlier, this toleration reflected the official belief that prostitutes provided a necessary outlet for the powerful lusts of working class men. It was also accepted because the women who provided this service were, from the point of view of the ruling class, the 'other' - working class women with values and behaviour markedly different from those of women of their own class. The sharp contrast between the speech, dress and behaviour of convict women and the demeanour of middle and upper class women also helped mask the extent to which sexual services were exchanged for financial gain across social classes. Because of this, convict society, particularly in the earlier decades, was noticeably more tolerant of women of 'easy virtue' amongst its upper echelons than was contemporary British society or later colonial society.

Deborah Oxley (1988, p.87) makes another important point in identifying prostitution as a structural part of the capitalist patriarchy which characterised colonising society. Working class women's role in this society was primarily to reproduce the working class: future, past and present. An intrinsic part of this role was the provision of sexual services to men, through marriage, force or payment. Sex was commercialised and turned into a commodity.

The convict era was thus crucial in setting the pattern for the history of prostitution in Australia. It saw the establishment of the sex industry as an important part of the life experience and work options of women within colonising society; it was also during this period that the extent of prostitution came to be used as a gauge of the worth of colonial women and of the success of colonial society more generally. Prostitution assumed a rhetorical and symbolic significance quite apart from its importance as an avenue for women's economic survival.

Prostitution on the Colonial Pastoral, Mining and Maritime Frontier

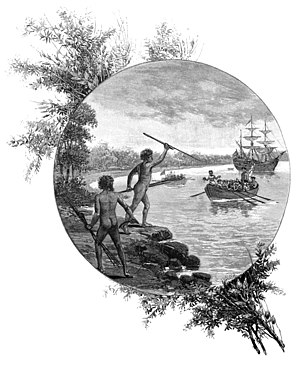

Meanwhile, as prostitution of European women flourished in the penal settlements, wherever the white colonisers intruded on Aboriginal lands sexual contact between white men and black women occurred soon after. In some cases this was the result of Aboriginal people extending traditional hospitality to visitors. That is, Aboriginal women were lent to the intruders in the expectation that friendly relations would ensue. In some cases, too, Aboriginal women became more regular companions for white men, often as a deliberate strategy to incorporate the newcomers into the Aboriginal kinship system. It was also, no doubt, sometimes a matter of personal preference on the part of Aboriginal women, who welcomed the novelty the white men provided and perhaps also wished to cast in their lot with the ascendant power in the region.

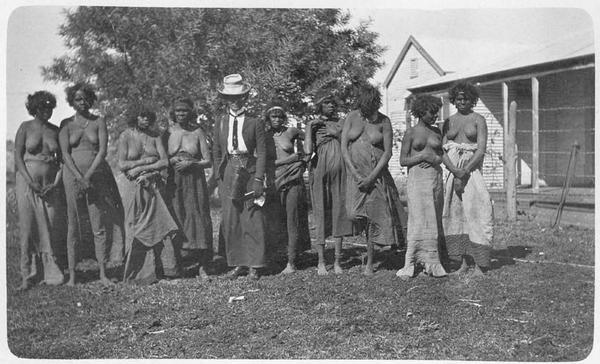

All too often, however, sexual interaction was coercive and violent, with Aboriginal women being conquered and taken in the same way that Aboriginal lands were. In the aftermath of dispossession Aboriginal women were often left with little choice but to engage in prostitution, either for money or for goods, in order to survive as individuals and to contribute to the survival of their kin. They formed the pivot of what Deborah Bird Rose (1992, Ch.19) calls 'an economy of sex'. As access to hunting grounds was increasingly prevented and sources of food became rapidly depleted, Aboriginal people were forced to participate in the white economy to survive. In the early colonial period, where convict labour was readily available, Aboriginal women's sexuality was often the only saleable item possessed by the survivors who eked out a precarious existence on the edges of white society. In the north, the labour of young men was also valued, but here the almost total absence of white women placed Aboriginal women in even greater demand. They were indispensable as domestic workers as well as performing a wide range of non-traditional women's work, such as stock work and mining, in certain areas. For all these workers, satisfying the sexual demands of their co-workers and bosses was usually considered part of the job. The more fortunate were able to obtain something in exchange for their sexual favours - such as extra rations which were shared with their kin in the camp. The less fortunate were treated as sexual slaves, confined for the use of white managers and stock workers. Ann McGrath (1984a, 1987) relates the Northern Territory practice of keeping a number of young 'stud gins' locked up in a chicken-wire enclosure as an enticement for white labourers, who were otherwise reluctant to work in the so-called 'womanless North'.

While this practice contributed to the economy of the pastoralists, the relatively benign practice of exchanging sex for extra rations contributed enormously to the survival of Aboriginal groups dispossessed by pastoralism and mining or living in areas where the bush tucker was radically depleted.

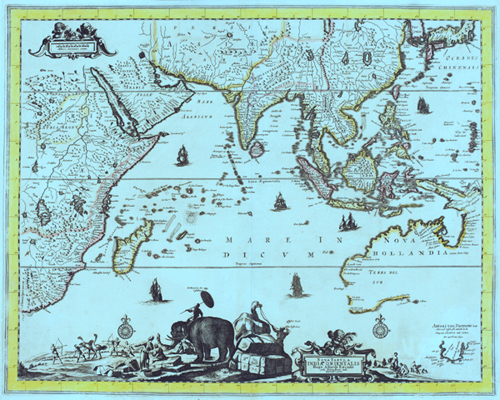

But it was not just Aboriginal women who were engaged to satisfy the lusts of men in the North. In the late nineteenth century Japanese and, to a lesser extent, Europeans and Australians operated brothels, especially in ports and mining centres. The more southerly the location the greater the proportion of Australian and European women and the fewer the Japanese found in sex work. The earlier goldrushes in Victoria and New South Wales, by contrast, were served almost entirely by prostitutes from Britain and Australia. Japanese brothels were a prominent feature of waterfront life in ports such as Broome, Darwin and Thursday Island, where the inmates catered for the wide range of nationalities engaged in the pearling, pearl-shell and fishing industries, as well as those employed on cargo and naval vessels. The role these women played in the economic life of the ports was as great as their contribution to its social facilities. Brothel-keepers were often in partnership with pearl fishermen, the proceeds of prostitution being used to finance the purchase and outfitting of Japanese pearling luggers (Hunt, 1986; C. Moore, 1992; Sissons, 1976-77).

Aboriginal women were also involved in prostitution in the maritime industry, though their case is somewhat special. In Western Australia, for instance, until legislation in 1871 prohibited the practice, they were employed both as divers and prostitutes on the pearling luggers which operated out of ports such as Broome and Roebourne (Hunt, 1986; Reynolds, 1990). On shore, women from local areas and others abandoned by drovers, miners or troopers far from their own country, waited in the mangroves at the river mouths to sell their wares to the fishermen as they came ashore with their earnings. Again, state intervention attempted to outlaw this practice. It would be naive to think, however, that legislation put a stop to the trade in Aboriginal women's sexuality. This continued, albeit in a more clandestine fashion.

The frontier has had a special legacy in the way in which prostitution is treated by sections of Australian society into the present. There is still a certain 'out of sight out of mind' mentality regarding sexual relations between women of Aboriginal descent and non-Aboriginal men which extends to commercial sex, especially in rural areas. For most of the twentieth century Aboriginal women were controlled by the various state 'protection Acts' rather than the civil and criminal laws which were used to police non-Aboriginal prostitution. They were thus put in a separate category to other prostitutes. In some ways this had negative consequences for the women concerned, since the powers of the Chief Protectors of Aborigines were far more far-reaching than those of the police in relation to non- Aboriginal prostitutes (Huggins and Blake, 1992). In other ways their separateness was more positive. The fact that Aboriginal women usually traded sex in fringe-camps or on isolated stations rather than city streets meant that they escaped many of the moves by police and criminal organisations to control their activities and earnings. The balance of these factors must have varied considerably with the experience of individual women.

The frontier years also had ramifications for non-Aboriginal sex workers. The legacy is clearly evident in mining towns such as Kalgoorlie, where prostitution is openly carried on under the virtual supervision of the police. As in colonial days, the police (and apparently the majority of the local community) consider the brothels a necessary part of life in a mining town where men still outnumber women. This acceptance and semi-official control has been a mixed blessing for the women concerned. The vigilance of the police ensures that criminal elements are kept away from the brothels and their inmates, making sex work in Kalgoorlie much safer than probably anywhere else in Australia. However, this security comes at the price of excessive intrusion into the personal relationships and movements of sex workers. As one former Kalgoorlie prostitute recalled of her years in a Hay Street brothel in the 1970s, after fleeing Sydney because of violence from the 'big fellas': 'Oh no, you weren't allowed to have boyfriends. Not in Kalgoorlie... The police won't let you... I tell you what, I couldn't cop that, not being free' (Frances, 1993, p.14). In addition to having their personal relationships vetted, sex workers were forbidden to shop in the town after midday and were not allowed to use the local restaurants, hotels, swimming pool or cinemas or to go to the racecourse. This situation persists to the present day (Cohen, 1994).

3:18

3:18

+copy.jpg)

+copy.jpg)

http://www.creativemeat.com/tag/free-music-synthesizer/

http://www.creativemeat.com/tag/free-music-synthesizer/

The song made famous by the late Slim Dusty, was first written in the original Day Dawn Hotel in Ingham in north Queensland in 1943, by an Irish cane cutter Dan Sheahan, after some American soldiers drank the pub dry the previous night. > >

The song made famous by the late Slim Dusty, was first written in the original Day Dawn Hotel in Ingham in north Queensland in 1943, by an Irish cane cutter Dan Sheahan, after some American soldiers drank the pub dry the previous night. > >

2:03Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace.

2:03Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace. ww.youtube.com/watch?v=UJgciC1j-r0

ww.youtube.com/watch?v=UJgciC1j-r0

Ric Williams, blog editor Home

Ric Williams, blog editor Home

Ric Williams, blog editor.

Ric Williams, blog editor.

Home........................................

Home........................................ Older Posts

Older Posts

G

G

.jpg)

highlight

highlight