Lesbians were rife in the 18th century.

Lesbians were rife in the 18th century.

For those who failed, London was unforgiving, and they ended up in the impoverished ghettos to the east. Just a few minutes' walk away from what is now the busy shopping district of the modern West End was one of the vilest slums in London: St Giles. 'The houses at St Giles were called "rookeries" because that suggested people packed into nests,' says Professor Dabydeen. 'It was a place of the marginalised and destitute, of pickpockets, of murders, rapes, illegal gambling, cockfighting – any imaginable human depravity took place in St Giles.'

The vast gulf between rich and poor fuelled crime rates, and fear of crime obsessed the rich. Newspapers – another new phenomenon – were passed round coffee houses and regaled their readers with sensational stories about highwaymen, murderers and executions. And the focus for wealthy Londoners' anxieties about crime was St Giles. Paranoia about this wretched quarter reached fever pitch in the early 1700s, when the urban poor seized on a terrifying new vice – gin.

Gin

The gin of the 18th century bore no relation to the respectable expensive spirit of today. A Dutch import, Madam Geneva (as she was called) was cheap and lethal. 'This new drink from Holland suddenly arrived among a people who weren't used to drinking spirits,' says Patrick Dillon. 'The strongest thing they had drunk before was strong beer, and suddenly for a penny a dram they could get this fantastic new drug. Stronger than anything they'd tasted before, it would instantly get them drunk. There was a famous signboard over gin shops that said: "Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence, straw for nothing" – of course, you got the straw to crash out on once you had drunk too much.'

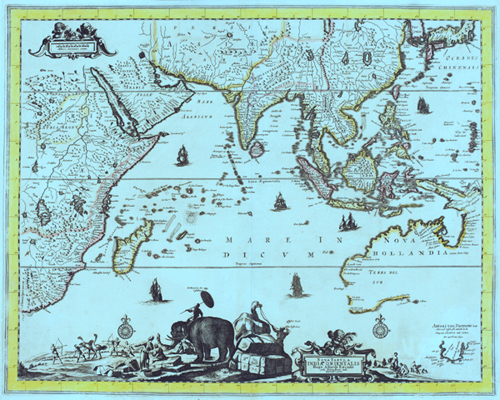

Numbers of Convicts (1788 - 1868) More than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868.

More than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868.

About 80,000 convicts were sent to New South Wales (NSW), including a few to Port Phillip (future Melbourne) and Moreton Bay (future Brisbane) which were part of NSW until 1851.

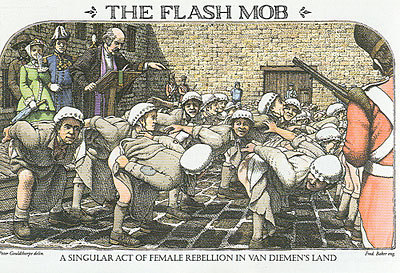

Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) received 69,000. The last convicts to land in eastern Australia were in Tasmania in 1852.

However, Western Australia (WA) only started receiving convicts in 1850 and continued to 1868. 9,700 convicts were sent to WA to help its very small population to build public buildings. There were no female prisoners transported to Western Australia. No convicts were sent to South Australia (SA).

However, Western Australia (WA) only started receiving convicts in 1850 and continued to 1868. 9,700 convicts were sent to WA to help its very small population to build public buildings. There were no female prisoners transported to Western Australia. No convicts were sent to South Australia (SA).

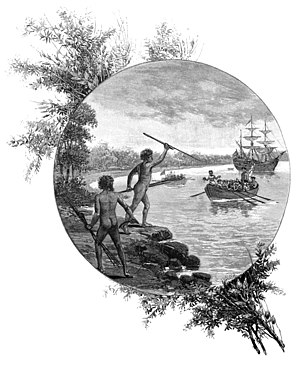

Some 1040 ships carried convicts from England and Ireland and other places to Australia. It is thought that about 165,000 departed from the ports of embarkation, and 3,000 died en route (some of the numbers were taken from Southern Cross Genealogy).

- Image: Fremantle prison, built by convicts

- The reasons for transportation to Australia

In the eighteenth century (sometimes called the 1700s), the gap between rich and poor was huge. In England, King George III (cf. image on the left) lived in his palace on the rich side of London, while in the east of the city most people were poor and hungry.

People began their working lives at the age of six, labouring long hours in factories for small wages.

Men had to live close to their workplaces, so hundreds of families would be crowded into just a few streets near butcher’s shops and tanneries, where leather was made. The waste from these places, as well as sewerage from the houses, often ran openly in the street. Disease was very common in these slums. Nobody thought that life would get any better, so men and women tried to forget their troubles by getting drunk on cheap alcohol.

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment