Why we left Wales* Three Generations of Welsh Miners (1950) © W. Eugene

Three Generations of Welsh Miners (1950) © W. Eugene

From Welshpedia

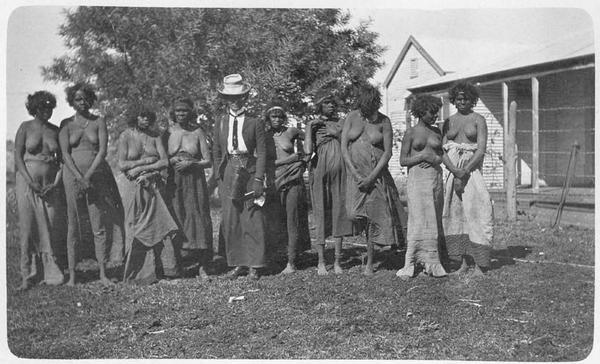

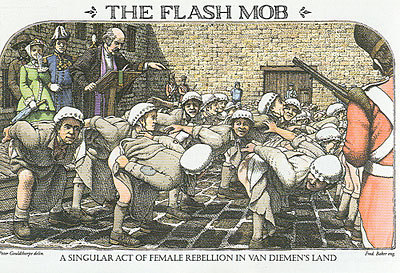

Hello fellow Cymbrai, when we left Wales most people spoke the old language. That was in 1787. It was a poor downtrodden place then and it was lucky my gr gr gr gandfather deserted the English army, into which he had been forced and thereby became a convict and was sent to Australia. If you want to know the story then look up "Our Williams Story" Australia. Life was harsh in the new land but nobody considered going back to the British Isles (that we know.)

Using the word Wales and Welsh is a shameful thing. Names that were imposed, just as the Germanic language (English) was imposed, that unhappily we are now using. It is a country that had a prince imposed who has never been a Cymbrai but is (at present) a Teuton with a bit of Scott, a foreigner. The people were distrusted by the English and had to toil in the mines coughing their lungs out in an early death.

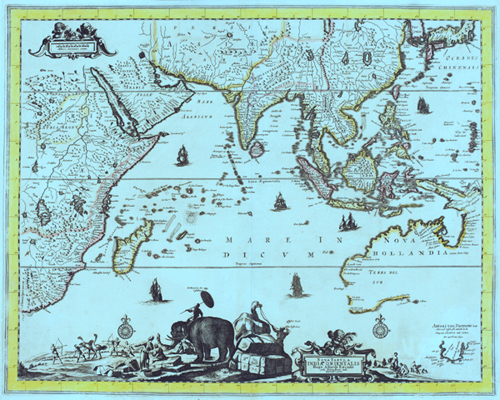

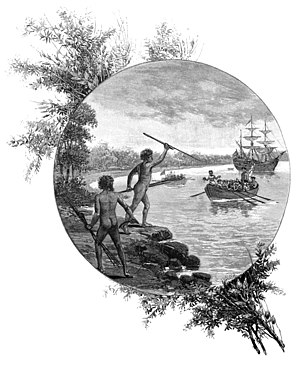

At about the time my ancestor left Wales in chains, there were still Cornishmen who spoke their understandable tongue and in Brittany our cousins carried on our ancient heritage. To the Spanish province of Galicia our tribe extended. Even in Poland and where is now the Czech Republic diminishing groups of us still survived. The story of Prince Madoc may be a legend, but the Mandan (Indians) had a language and culture that was Celtic in the fifteen hundreds around the Missouri and Mississipi.

Some historians say that these people speaking a Celtic tongue came over to America at the end of the last ice age. Professor Barry Fell, "America B.C." has a lot to say about that.

In more recent times the Welsh have emigrated to many parts of the world. even to Argentina where some towns are named after them and to the mines of British Columbia and the Rocky Mountains.

I have one of the most common names of Welsh origin, but I have heard it just mean one of the serfs of William, an Anglo-Norman lord imposed on the Welsh by conquest who stealing ourlands.

I am proud to be of Cymbraic extraction and it is a wonder we still have any national identity the way we have been treated over the centuries. I wish I could say goodbye and good luck to you all, but my ancient language is not known to me... Cedric Williams. (Now living in Canada.)

If you would be so kind as to link to us then please copy this logo to your web site and link using http://www.welshpedia.co.uk/wiki/wales/index.php/Main_Page

The Brecon Beacons and the Brecon area have a long history of human habitation. Early settlements were mainly on the hill tops as the valleys would have been regularly flooded and covered in dense forest.Evidence has been found of the manufacture of flint tools on the castle site, dating back 4000 to 5000 years. North West of the hotel is the remains of Pen-y-crug, an Iron Age hill fort. It may well have been occupied when the Romans arrived - Two miles to the west of Brecon lies Y-Gaer. a roman fort covering nearly 5 acres - The fort was built around 5O AD and may have been occupied as late as 300 AD. The first regiment in occupation probably came from North West Spain. Brecon was a Roman cross-roads and some roman roads remain visible on the Beacons even today.

In the fifth Century the local ruler is said to have sent his daughter to Ireland in search of a husband. Many of her retinue of guards died on the journey. She found her Irish Prince their son, Brychan, was sent to Wales to grow up at the Court of his grandfather. It is from the name 'Brychan' that the old country name of Brysheiniog and later 'Brecon' was derived. One of his daughters, called Tudful was killed by Barbarians. The welsh for martyr is merthyr, hence the settlement of Merthyr Tydfil 20 miles to the south got its name.

Brecon castle and town are Norman in origin. The castle came first and was the creation of Bernard de Neufmarche. He took his surname from the village of Neufmarche near Rouen, the capital of Normandy. He was of the second generation of conquerors who extended Norman influence into the Marches of Wales. By 1093 de Neufmarche and his knights had defeated the Welsh rulers of south Wales and began to build themselves the castles from which they intended to control their new lands.

|

The earliest castle was on the type known as a motte and bailey. The great earth mound, now in the Bishop's Palace garden, opposite the hotel, was the motte on top of which there was originally a timber keep. The bailey or courtyard below the motte extended to cover the present garden and, presumably part of the site of the hotel; the embankment on the north side can be clearly seen in the garden. Even in this early stage the castle must have been a daunting sight. This is exactly what the Normans intended; a deterrent to subdue the hostile Welsh.

However not all the buildings associated with this early castle were military in appearance or function. A charter of c.11OO provides information about the growth of the civilian settlement which soon accompanied the castle. By this charter Bernard de Neufmarche granted lands and privileges to the monastery which he established just to the north of the castle. This Benedictine Priory occupied the site of the present cathedral. He gave the monks the profits from two corn mills; one on the Usk, which was near the weir at the end of the promenade, the other was at the foot of the hill below the castle. This is now occupied by a veterinary surgeon. The grant also included burgages within the castle. A burgage was a unit of land in a medieval town. The significant point here is that this first reference to a civilian settlement in Brecon locates the site inside the castle.

|

What did Brecon castle look like at the height of its importance in the medieval period? Unfortunately there is no drawing earlier than Speed's (of 1610) and very little archaeological work has been done on the site. Consequently what follows is based on documentary references, the surviving fabric and comparisons with other castles which have survived in more complete form.

There. were two entrances as well as the postern gate. The main gate faced west and overlooked the Usk. It was approached across a drawbridge and probably guarded by two semi-circular towers and the usual great door and portcullis. From the town direction the castle was also guarded by a drawbridge on the site of the present bridge which crosses the Honddu. These gates were joined by the encircling curtain wail. which enclosed the whole area of the castle. Within these outer defences the most imposing building was the great Hall; this was the social centre of the castle and the Lordship where the Lords of Brecon held court when in the area. (The surviving medieval halls at Christ College - across the river from the castle - give a good idea of what it must have looked like inside. The private apartments of the Lord were next to the Hall. There are references to other rooms and buildings in the medieval documents. For example the Constable and the Receiver (of taxes and dues) had their own chambers. There was a chapel, exchequer, kitchen, harness tower, stable and porter's chamber. The well was described as being 30 feet deep. These buildings suggest that the castle was more like a bustling town than the romantic, military fortress of imagination. People from the surrounding Lordship came to the courts held at the castle, they paid their dues to the exchequer, they pleaded for privileges or came with supplies of food, timber and other necessaries.

Nonetheless there were many occasions when the drawbridges were raised and the castle played its military role as an alien strong point in a hotly disputed part of the country. It was attacked six times between 1215 and 1273; three of the assaults were successful - in 1215, 1264 and 1265. Much of this warfare was part of the three hundred year struggle between the Normans and the Welsh which began with the conquest and lasted until the Glyndwr revolt. There was another cause of war in the Marches -the power struggles involving Kings and their barons. The military events which affected the castle and the town in the thirteenth century must be seen in this wider, national context.

Marcher Lordships differed from the rest of Britain. Lords were able to set up their own system of law, they were, in effect. petty Kings. The King had little right to interfere in internal affairs of the Lordship unless the Lord were guilty of treason or felony.

For the Lords of Brecon were among the most powerful men in the. Kingdom. Their possessions in this area were only a part of their vast lands. De Neufmarche was succeeded by his daughter Sybil who married the Earl of Hereford. Their Brecon estates passed to William de Braose. They remained in the de Braose family for about a hundred years then by marriage the Brecon and Hereford lands of the original Lordship were united in the possession of Humphrey de Bohun. The Lordship was in royal hands from the late fourteenth century to the middle of the fifteenth when it was granted to the Staffords who were to be the last Lords of Brecon. All these families were ambitious politically and this involved them in wars, rebellions and conspiracies. For this reason Brecon in the middle ages was often caught up in important events and was much closer to great national issues than in later centuries.

The careers of the two last Dukes of Buckingham illustrate this vividly. Henry Stafford. the second duke, had been a supporter of Richard 111 but they had fallen out and Henry retired to his castle at Brecon. Here he plotted against the King. His accomplice was a prisoner at the castle, John Morton, Bishop of Ely. (After whom the Ely Tower and Ely place are named.) The duke raised an army to oppose the King but his rebellion failed and he was executed. The bishop fled abroad and joined the Earl of Richmond who was soon to defeat Richard 111 at Bosworth and to become the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII. The King employed the bishop as one of his most efficient tax collectors; he was the Morton of Morton's fork : The new King also rewarded the Stafford family for their loyalty. Edward, born in Brecon castle in February 1478, was granted all the honours, titles and lands which had belonged to his father. However the second Tudor found it necessary to execute this the third and last duke. In 1521 Buckingham very rashly flaunted his royal connections and claim to the throne. At the time, when Henry VIII had no legitimate heir.

This was tantamount to treason and was punished accordingly - So perished the last of the Lords of Brecon. By now the Tudors were determined to eliminate the quasi-independent powers which such magnates had enjoyed. By acts of parliament passed in 1536 and 1543 the Marches were finally brought under royal control. In place of the Lordship of Brecon there appeared the County of Brecknock

These changes together with a revolution in building styles and standards meant that the age of the castle was also over The Tudor peace allowed landowners to put a higher premium on comfort than security. Great houses began to replace draughty castles. It is ironic that when the castle entered this period of decline there is more information about its condition and appearance than when it was a powerful fortress. A survey of the buildings carried out in 1552 contains many references to the repairs which were necessary. The roofs lacked lead and much of the timber needed replacing. However Speed's map shows a mighty castle in 1610. But many of the buildings on his map are symbols rather than accurate representations of what was there In 1645 a Royalist referred to the castle and town walls as having been demolished by the inhabitants; presumably to prevent Brecon being strongly fortified and thus suffering a damaging siege. His remarks are exaggerated because later writers and artists describe the castle as an impressive ruin. The drawing by Buck, dated 1741, is the best example.

Parts of the castle were put to use. For example the chapel -dedicated to St. Nicholas - was a goal until 1690 when it was demolished. Further information is provided by estate maps of the town which were drawn in the second half of the eighteenth century. A map Of 1761 shows the great Hall with its windows and to the west a building with two chimneys. North of this is a rectangular enclosure. On a plan drawn twenty years later this is described as a Bowling Green - The state of the castle ruins continued to deteriorate and was the object of disparaging comments by visitors to Brecon. For example 'The Cambrian Traveller's Guide & Pocket Companion of 1808' referred to the magnificent Castle.. (which) is now curtailed to a very insignificant ruin; and that little is so choked up and disfigured with miserable habitations, as to exhibit no token of its ancient grandeur.'

However this sad situation was soon to change - The Morgan family of Tredegar Park had extensive Breconshire connections and their attention was now turned to the castle and the house adjoining. Work on repairing the house began in 1809. During the next few years considerable sums of money were spent turning house into hotel. A steel engraving of this date gives a detailed view of the building which is clearly recognisable as the present hotel -(The engraving was done by Bourdon one of the numerous French prisoners-of-war held in Brecon during the Napoleonic wars.). The success of the Morgans' investment can be gauged by the prominence given to the Castle Hotel in later guides. By 1835 an impressive list of coaches called at the Castle Hotel; journeys to London on the Royal Mail, to Aberystwyth, Bristol, Carmarthen, Llandrindod.

Kindly written by Edward Parry, Christ College, Brecon. 1988

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment