The Investigator Tree:

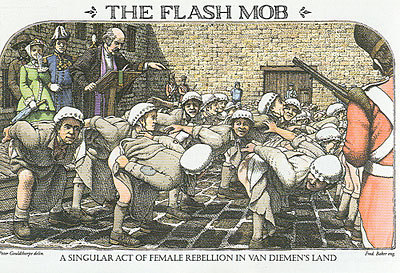

Eighteenth century inscriptions.

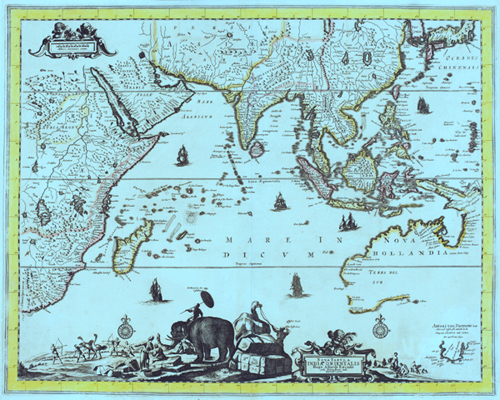

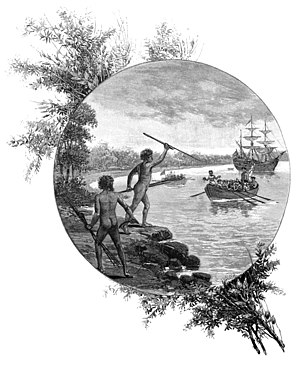

For centuries Indonesian fishermen have exploited resources along the north of the Western Australian coast and also around the islands and reefs located off this coastline. They have targeted a range of species including beche-de-mer (trepang or sea cucumber), trocus, seabirds (particularly frigate birds), seabird eggs, sharks, marine turtles, clams and various molluscs. There has been some subsistence fishing but the majority of the product has been collected for sale on the Asian market. Trocus shells are used in the manufacture of buttons and dried beche-de-mer and sharkfin are sought after food products through much of Asia.

Traditional fishers had no navigational equipment and many set a course from Indonesia using land marks. When some distance out to sea they would then head for the clouds which form above Ashmore Reef. At Ashmore they replenished water from the fresh water wells and collected birds and eggs for food. From here they sailed to the islands and coastline further south.

In 1933 an unattributed article in the Brisbane weekly newspaper the Queenslander, undoubtedly following Palmer's imaginative lead, referred to 'Chinese letters' on the tree, made in 1798 when a junk was wrecked on Sweers Island. Twenty-five of the Chinese trepang fishermen on board the vessel lived on the island, the article also claimed, until rescued by a 'Macassar prau'. It is unclear, however, why shipwrecked Chinese or their Macassan rescuers would carve the date into a tree using a foreign script! According to the same article, and again following Palmer, a Dutch exploring vessel, commanded by Tasman, called at Sweers Island in 1781, and the name of that vessel--here the Loury--was carved into the trunk of the Investigator Tree. The writer of this article almost certainly used as his principal source, and embellished somewhat, Palmer's account of the Investigator Tree inscriptions published thirty years before.

Several magazine articles published in the 1940s refer to the Investigator Tree and to an inscription in Chinese supposedly carved on it. One, by E.D.F. in 1942, claims that the crew of the Investigator found a tree on which 'were carved some Chinese characters and the date, 1798, evidence of visits by Asiatic beche-de-mer fishers'. In addition, the 'remains' of a wrecked junk and signs of brief visits of early Dutch ships' were found. (8) In a similar vein, G. P. in 1946 claims that Flinders found evidence of the visit of Chinese to Sweers Island: 'he found a tree on which were carved some Chinese characters and the date, 1798'. Flinders then 'carved the date and name of his ship on the same gnarled old tree on which he found the Chinese characters'. (9) Another article, by 'Ringata' in 1943, rightly describes the Investigator Tree carvings as a 'romantic link with three early navigators', but then continues to claimIn 1841, John Lort Stokes, commanding H.M.S. Beagle, was exploring Australia's northern coastline, and in July he arrived at the small island in the Gulf of Carpentaria (Lat. 170o6'S Long. 139o37'E) which Matthew Flinders, nearly forty years before, had named Sweers. On the western side of this island Stokes discovered a tree with the name of Flinders's ship, the Investigator, carved along the trunk in large letters. This discovery excited Stokes who wrote of it thus:

- It was our good fortune to find at last some traces of the Investigator's voyage, which at once invested the place with all the charms of association, and gave it an interest in our eyes that words can ill express. All the adventures and sufferings of the intrepid Flinders vividly recurred to our memory. (1)

In February 1889, the tree became the property of the Queensland Museum. (2) It is presently displayed in the Museum of Lands Mapping and Surveying in Brisbane.

By the time the Investigator Tree was brought to Brisbane it bore not only the name of Flinders's ship, but also that of the Beagle, which Stokes had added in 1841. In addition were a large number of other names, including some dating from A.C. Gregory's North Australian Expedition in 1856, and some from the Burke and Wills Search Expedition under William Landsborough in 1861. Indeed, the tree carried inscriptions representative of many phases in the history, not just of Sweers Island, but of northern Australia generally. This makes the Investigator Tree an historic artifact of great cultural importance. A detailed historical interpretation of the inscriptions on the tree has been compiled by Saenger and Stubbs. (3)

Besides the many inscriptions which were added to the tree after the visit of Flinders in 1802, many published articles and books have expressed the intriguing idea that the tree also carried inscriptions of Dutch and Chinese origin, predating Flinders's visit. In fact, in almost every account of the tree published after its arrival in Brisbane - and they number at least ten, spanning over eighty years - claims have been made for Dutch and Chinese inscriptions. Curiously, only one item from before 1889 makes any such suggestion. This paper tests these relatively recent claims that the Investigator Tree carried inscriptions predating the 1802 visit of Matthew Flinders to Sweers Island.

According to Reed in 1973, in an entry entitled 'Sweers Island Q' in his Place Names of Australia, Dutch and Chinese navigators left inscriptions on [the Investigator Tree] at various times' prior to the visit of Flinders to the island in 1802. (4) This is a relatively recent perpetuation of the idea that the Investigator Tree carried pre-Flinders inscriptions. The idea which lacks any obvious basis in fact. In order to discover the origin of this apparent myth, its history, which encompasses more than a century, is subjected here to close scrutiny.The earliest reference we have discovered to pre-Flinders inscriptions on the Investigator Tree is in a report on explorations undertaken in the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1880. The Queensland Government Schooner Pearl, under the command of Captain Pennefather, was sent that year to chart the waters around Point Parker on the western side of the Gulf. The Pearl arrived at Sweers Island on 15 September. Pennefather found the tree and later reported that 'on [it] is to be seen the name of H.M.S. Investigator with the date 1802, and a still earlier date, supposed to have been carved by the Dutch'. (5) It is unknown whether Pennefather himself made this supposition, or whether he was attributing it to some unnamed informant. If the former is true Pennefather himself may be the originator of the Dutch inscription myth; if the latter, he may only have been following an older tradition.

Pennefather's reference to the supposed Dutch inscription was reiterated in 1895 by Major A.J. Boyd in a narrative based on the official reports of Pennefather's 1880 explorations in the Gulf. (6) Boyd read his paper at a meeting of the Queensland Branch of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia in November 1895. Between Pennefather's voyage and this time, the trunk of the Investigator Tree had arrived in Brisbane where it was placed on exhibition in the Queensland Museum, and it is probable that Boyd's narrative, through its timing and greater accessibility, influenced thinking about the tree more than Pennefather's earlier but more obscure official report. In this way the idea of a Dutch inscription on the tree may have received a considerable boost.

In 1903, in his posthumously-published Early Days in North Queensland, Edward Palmer presented a summary of the names and dates carved on the Investigator Tree. (7) The oldest inscription, Palmer claimed, with the date 1781, was the name of a Dutch exploring vessel the Lowy--allegedly commanded by Captain Abel Tasman, which called at Sweers Island in that year. Unfortunately for Palmer, the three ships under Tasman's command during his exploration of the Gulf were named Limmen, de Zeemeeuw, and de Bracq, and his voyage took place in 1644, not 1781. Although not the earliest reference to a Dutch inscription, Palmer's was the first we have found which gives a date, and is the first to use the name Lowy. It is not known where Palmer obtained this information, but Pennefather's report certainly provided no such detail. Thus, Pennefather's modest 1880 supposition was developed to great heights of extravagance in Palmer's later account.

Not only did Palmer elaborate the earlier suggestion of a Dutch inscription, but he added a claim for the existence of a Chinese inscription on the tree. The second oldest marking on the tree, Palmer said, comprised 'some Chinese characters' and the date 1798. Palmer is thus the earliest known perpetrator, and therefore perhaps the originator, of the Chinese inscription myth.

In 1933 an unattributed article in the Brisbane weekly newspaper the Queenslander, undoubtedly following Palmer's imaginative lead, referred to 'Chinese letters' on the tree, made in 1798 when a junk was wrecked on Sweers Island. Twenty-five of the Chinese trepang fishermen on board the vessel lived on the island, the article also claimed, until rescued by a 'Macassar prau'. It is unclear, however, why shipwrecked Chinese or their Macassan rescuers would carve the date into a tree using a foreign script! According to the same article, and again following Palmer, a Dutch exploring vessel, commanded by Tasman, called at Sweers Island in 1781, and the name of that vessel--here the Loury--was carved into the trunk of the Investigator Tree. The writer of this article almost certainly used as his principal source, and embellished somewhat, Palmer's account of the Investigator Tree inscriptions published thirty years before.

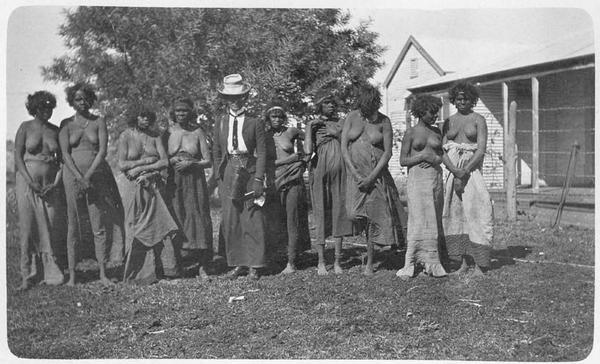

Several magazine articles published in the 1940s refer to the Investigator Tree and to an inscription in Chinese supposedly carved on it. One, by E.D.F. in 1942, claims that the crew of the Investigator found a tree on which 'were carved some Chinese characters and the date, 1798, evidence of visits by Asiatic beche-de-mer fishers'. In addition, the 'remains' of a wrecked junk and signs of brief visits of early Dutch ships' were found. (8) In a similar vein, G. P. in 1946 claims that Flinders found evidence of the visit of Chinese to Sweers Island: 'he found a tree on which were carved some Chinese characters and the date, 1798'. Flinders then 'carved the date and name of his ship on the same gnarled old tree on which he found the Chinese characters'. (9) Another article, by 'Ringata' in 1943, rightly describes the Investigator Tree carvings as a 'romantic link with three early navigators', but then continues to claim: Also on the trunk are a number of carved Chinese characters; it is believed that these were executed by members of the crew of a Chinese beche-de-mer fishing boat. (10)Then, two decades later, Lack wrote in 1962 that:Chinese characters, almost obliterated by time, on the famous Investigator tree from Sweer's [sic] Island, now in the Queensland Museum, would seem to indicate that Chinese junks came seeking beche-de-mer in the Gulf of Carpentaria at least half a century before Cook sailed along the eastern coast, and a hundred years before Flinders' Investigator visited these waters. (11) From 1933 onwards, the references to Chinese inscriptions on the Investigator Tree have in common their use of these supposed markings as evidence of the visit of Asian trepang fishermen to Sweers Island. There is better historical evidence for such visits, however, than for the alleged inscriptions, and it would have been more sound to use the visits to support claims for the existence of the inscriptions, not the reverse.How did these claims originate? The ingredients of the idea are contained in the history of the Dutch and Macassan presence in northern Australia. That Asian mariners visited the northern coast of Australia long before the first Englishmen did so is beyond doubt. The development prior to the end of the eighteenth century of a thriving Macassan trepang fishing industry along our northern shores was discussed in detail by Campbell in 1916 and analysed thoroughly in Macknight in 1976. (12) Although the industry was centred on the port of Macassar (now Ujung Pandang) on the Indonesian island of Celebes (now Sulawesi), the consumption of trepang was almost entirely restricted to the Chinese, and China was the final destination for most of the trepang exported from Macassar. It must be emphasised that the Chinese themselves did not do the fishing in northern Australia, contrary to this suggestion in many of the articles quoted above.Trepang became a common and substantial item of trade between Macassar and China by the late 1700s. According to Macknight, Dutch restrictions on Macassarese enterprise after 1667 probably caused the redirection of resources into new activities such as the trepang industry in general, and voyages to northern Australia in particular. Direct trade between Macassar and south China in the earlier part of the seventeenth century provided opportunities for trepang to become known there. In addition, the general outline of the Australian coast was known from Dutch charts of the time, facilitating Macassarese activity in that region.

The trepang industry probably began, in the opinion of Macknight, in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The absence of references to the Macassans in records of Dutch exploration of northern Australia prior to 1754, however, suggests that it began in a 'small, irregular and secretive way', but it had certainly become a large and flourishing industry by the end of the eighteenth century. (13) Thus, when in December 1802 Flinders visited the cluster of islands in the south-western corner of the Gulf which he named Sir Edward Pellew's Group, he found that:

Indications of some foreign people having visited this group were almost as numerous as those left by the natives. Besides pieces of earthen jars and trees cut with axes, we found remnants of bamboo lattice work, palm leaves sewed with cotton thread into the form of such hats as are worn by the Chinese, and the remains of blue cotton trousers . . . It is evident that these people were Asiatics, but of what particular nation, or what their business [was] here, could not be ascertained; I suspected them, however, to be Chinese. (14) Flinders had visited Sweers Island the previous month and there he found seven human skulls and a number of bones lying together near three extinguished fires. A square piece of timber, seven feet long, of teak, which according to the judgment of the carpenter had been a quarter-deck carling of a ship, was also found, thrown up on the western beach. Later, on nearby Bentinck Island, he saw the stumps of twenty or more trees, which had been felled with an axe or some other sharp iron instrument. Close to these were found scattered the broken remains of an earthen jar. From these several observations Flinders conjectured that a ship from the East Indies had been wrecked there 'two or three years back', that part of the crew had been killed, and that the others had 'gone away . . . upon rafts constructed after the manner of the natives'. (15) Notably, Flinders made no mention of having discovered a tree bearing the carvings of these or any other visitors to Sweers Island. Nor did Robert Brown, the naturalist on the Investigator, nor Peter Goode, the gardener, although both made careful botanical searches of the island. (16)The origin of these 'foreign visitors' was revealed to Flinders in February 1803 when he discovered at the Gove Peninsula, near the western entrance to the Gulf of Carpentaria, 'a canoe full of men' and 'six vessels covered over like hulks, as if laid up for the bad season'. Flinders had little doubt that these people were of the same origin as those whose traces he had already found 'so abundantly in the Gulph'. It was soon ascertained that the six vessels, which seemed to have twenty or twenty-five men in each, were 'prows from Macassar'. (18) Flinders communicated with their six Malay commanders and learned that sixty prows, carrying about one thousand men, had left Macassar in the north-west monsoon two months before and the fleet, divided into groups of five or six vessels each, now lay at various places along the coast. (19) The purpose of the expedition was to search for a marine animal called trepang, (20) which when dried and smoked was sold to the Chinese. Pobassoo, the chief of the division which Flinders encountered, had made six or seven such visits to the Australian coast during the preceding twenty years, that is since about 1782, and he claimed to be 'one of the first who came'. (21)

Stokes, who landed on Sweers Island in 1841, found no inscription on the Investigator Tree other than the one which he attributed to Flinders. Fifteen years later, Lieutenant Chimmo, of the paddle steamer Torch, landed there and discovered at high water mark on the western side of the island:

the remains of a Malay proa . . . the beams of which were teak. We concluded she had been cast away during the N.W. monsoon; her beam was 17 feet; length could not be ascertained. (22) He also found the tree which still 'plainly bore' the inscriptions of the Investigator, and of the Beagle which had visited the island in the meantime. (23) Like Stokes, Chimmo made no mention of any earlier carvings.Further evidence of the visit of Asian mariners to Sweers Island is provided by a record of the Queensland Museum having received in 1889 a 'piece of mast of a Chinese junk, supposed to have been wrecked on Sweers Island'. (24) The Queenslander claims that this was forwarded to Brisbane with the main branch of the Investigator Tree, and that it was part of the wrecked Chinese junk 'found' by Flinders. (25) It is unknown whether this is so (Flinders found only one piece of timber), whether it was part of the wrecked prow which Chimmo found in 1856 (assuming they were different wrecks), or whether it belonged to another more recent wreck.

Several elements of the claims discussed above for pre-Flinders inscriptions on the Investigator Tree seem to have as their bases comments made by Flinders in the account of his exploration of the Gulf quoted above. Flinders's conjecture in 1802 that a ship from the East Indies had been wrecked on Sweers Island 'two or three years back', (26) together with his supposition that the Asian visitors whose traces he found in Sir Edward Pellew's Group were Chinese, may be the basis of the claim for the 1798 Chinese inscription first made by Palmer in 1903. Flinders's observation that each of the prows which he encountered in 1803 contained twenty or twenty-five men may be the basis for the claim in the Queenslander that the crew of the wrecked 'junk' numbered twenty-five. The origin of the claim that a Dutch exploring vessel called at Sweers Island in 1781 is not clear, but there may be some significance in the comment by Pobassoo, as recounted by Flinders, that he had made six or seven visits to the Australian coast during the preceding twenty years - since about 1782.

Several Dutch ships are known to have explored the waters of northern Australia from the early seventeenth century - notably those under the command of Tasman in 1644. That any actually visited Sweers Island is, however, unlikely. Tasman's are the only Dutch ships known to have sailed close to Sweers Island, but it is highly improbable that they stopped there. On Dutch maps showing Tasman's route around the Gulf, the Wellesley group of islands to which Sweers belongs appears as a peninsula--Cape van Diemen. Clearly, Tasman failed to recognise the individual islands of this group. (27) It is therefore inconceivable that he visited the western side of Sweers Island where the tree stood. The idea that he went ashore, and found the tree, (28) and carved a name on it, is sheer fantasy.

Although it therefore seems improbable that the Dutch visited Sweers Island, it is equally clear that Macassan trepangers had been there, both before Flinders, and probably on later occasions as well. It is still a big leap, however, from knowing of these visits to claiming the presence of Macassan inscriptions on the Investigator Tree. Flinders, whose record of his 1802 visit to the Gulf is meticulous, found no cause to comment about pre-existing inscriptions on the tree on which the name of his ship was carved in 1802. In 1895, the year in which Major Boyd presented his narrative of Captain Pennefather's voyage, there appeared in Brisbane the first edition of J.J. Knight's In the Early Days: History and Incident of Pionee

http://islamicsydney.com/story.php?id=177#north

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment