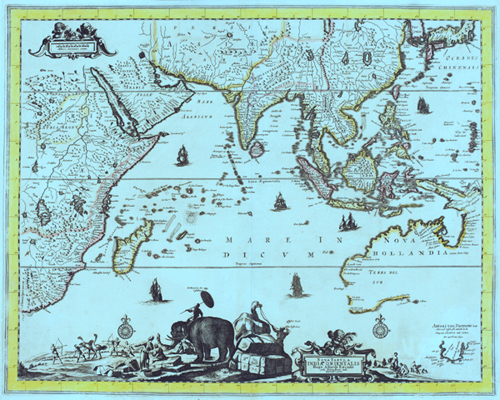

chapter 5 Arthur Phillip journal of first fleet to Botany Bay

| The gusts which descend from the summit of Table Mountain are sufficient to force ships ... 12 November 1787. On the 12th of November the fleet set sail, ...

australiaexplorers.com/arthurphillip/ |

table of contents Arthur Phillip journal of first fleet to Botany Bay

First Fleet Voyage to Botany Bay. Introduction; Table of ... Report of the Marines and Convicts under medical treatment, June 4, 1787; Chapter IV. ... australiaexplorers.com/arthurphillip/http://gutenberg.net.au/explorers.html

William Nash my gr gr gr grandfather took a "wife' Maria Haynes my gr gr gr

grandmother for the voyage to Botany Bay in 1787. Maria was probably a convict . We don't know what they looked like.What is quite certain, however, is that no women were actually transported for whoring, because it was never a transportable offense. The vast majority of female convicts, more than 80 percent, were sent out for theft, usually of a fairly petty sort. Crimes of violence figured low among them, as one might expect--about I percent. Sentences of more than seven years were exceedingly rare. None of this, given the severity of the English laws, suggests at the outset a very high degree of moral profligacy.

http://www.janesoceania.com/australia_history/index1.htm http://gutenberg.net.au/pgaus.html|

In the 18th century, a British woman was sentenced to transportation

to the British

penal colony of Australia. Her crime? Stealing 12lbs of Gloucester

cheese. Little did

she know that she was one of the founders of a nation.

However, as some anti-Pom (anti-British) Australians would

have you believe

today there were no political prisoners, no rabble rousing, hay

stackburning

activists or trades unionists sentenced for their subversive*

activities. Nor,

contrary to another common belief, were there any

prostitutes as such -

because prostitution was not a transportable offence

at the time.

The founding fathers of Australia: The story of convicts

shipped to the New World

By TONY RENNELL

26th July 2007

Daily Mail

This week archives revealed two million Brits - one in 30 of us - are descended

from the convicts deported to Australia. Here we tell the shocking stories of

depravity and despair on the very first convoy that took them to the

new world

Poor Elizabeth Beckford. She was 70 years old and her crime

was stealing 12lb of

Gloucester cheese.

For that she could have hanged. Hundreds did in those violent,

vengeful days, dancing

"the Tyburn frisk" in the words of those who crammed around the

gallows to watch this

favourite spectator sport of 18th century Britain. But the state, in its

mercy, saved her

life - and gave her a punishment that some would see as worse than

death.

She was an unwilling passenger on a fleet of 11 ships that set out from

England in 1787,

the first of the convoys of the criminal underclass - as the ruling elite

of Georgian

England saw them - sent in chains to colonise new and dangerous

shores on the

other side of the world.

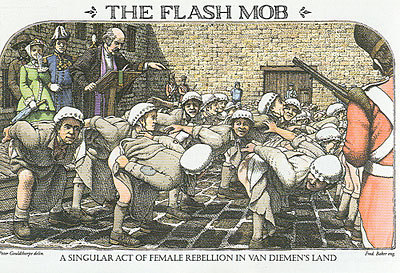

Women transported

to Australia were treated as whores.

Those 736 sad souls on that pioneering voyage would establish a new

world. Though

she didn't know it - and the thought would have given her no consolation

as she lay

crammed with others in

cell-like spaces below decks - Elizabeth was a founder member of a

new country,

Australia.

On Thursday, more than 200 years later, those who made those

dreadful voyages -

163,000 in all over the years to come - are feted. Twenty-first century

Australians

celebrate their convict past,

taking their lead from premier John Howard, a descendant of

transported folk on both

sides of his

family.

The shipping and court registers of the banished have long lain in

the National Archive

in London.

Now, in the knowledge that two million of us in Britain probably

have blood links

with

Australia's criminal forebears, they have been put online for

the hundreds of

thousands

of amateur genealogists in this country, eager to find out

more about their roots.

The history they hide may not be pleasant. Elizabeth, incredibly,

was not the

oldest on

that first ark of despair. Dorothy Handland, a dealer in rags and

old clothes, was 82. How

she was expected to contribute to empire-building in a virgin land

whose hardships could

only be guessed at is a mystery as great as the place she was

being sent to.

But nonetheless she was among the waggon-loads of prisoners dragged

down to the docks in

Portsmouth from the sunless ship hulks at Woolwich where they had

been held because the

prisons were all full. They were dressed in rags, their faces pale

from imprisonment,

louse-ridden and thin as rakes from the slops they had been

forced to live on.

Alongside the grannies were 120 other women, mostly young,

like 22-year-old

Elizabeth

Powley. Penniless at home in Norfolk she had raided someone's

kitchen for a

few shillings'

worth of bacon, flour and raisins and "24 ounces weight of butter

valued 12d"

(twelvepence).

The death sentence on this starving girl was commuted and,

as Robert Hughes

, historian

of the transportations, notes wryly in his book, The Fatal Shore,

"she was sent

to Australia,

never to eat butter again".

Women transported

to Australia were treated as whores.

Those 736 sad souls on that pioneering voyage would establish a new

world. Though

she didn't know it - and the thought would have given her no consolation

as she lay

crammed with others in

cell-like spaces below decks - Elizabeth was a founder member of a

new country,

Australia.

On Thursday, more than 200 years later, those who made those

dreadful voyages -

163,000 in all over the years to come - are feted. Twenty-first century

Australians

celebrate their convict past,

taking their lead from premier John Howard, a descendant of

transported folk on both

sides of his

family.

The shipping and court registers of the banished have long lain in

the National Archive

in London.

Now, in the knowledge that two million of us in Britain probably

have blood links

with

Australia's criminal forebears, they have been put online for

the hundreds of

thousands

of amateur genealogists in this country, eager to find out

more about their roots.

The history they hide may not be pleasant. Elizabeth, incredibly,

was not the

oldest on

that first ark of despair. Dorothy Handland, a dealer in rags and

old clothes, was 82. How

she was expected to contribute to empire-building in a virgin land

whose hardships could

only be guessed at is a mystery as great as the place she was

being sent to.

But nonetheless she was among the waggon-loads of prisoners dragged

down to the docks in

Portsmouth from the sunless ship hulks at Woolwich where they had

been held because the

prisons were all full. They were dressed in rags, their faces pale

from imprisonment,

louse-ridden and thin as rakes from the slops they had been

forced to live on.

Alongside the grannies were 120 other women, mostly young,

like 22-year-old

Elizabeth

Powley. Penniless at home in Norfolk she had raided someone's

kitchen for a

few shillings'

worth of bacon, flour and raisins and "24 ounces weight of butter

valued 12d"

(twelvepence).

The death sentence on this starving girl was commuted and,

as Robert Hughes

, historian

of the transportations, notes wryly in his book, The Fatal Shore,

"she was sent

to Australia,

never to eat butter again".

Many of those that weren't sentenced to hang at Tyburn's dreaded

tripod-shaped "Triple Tree"

gallows in London were instead transported to the Australian penal colony. Those people

probably would have preferred to hang.

Many of those that weren't sentenced to hang at Tyburn's dreaded

tripod-shaped "Triple Tree"

gallows in London were instead transported to the Australian penal colony. Those people

probably would have preferred to hang. |

jpg" src="http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/6a/Miss_constable_ 1787.jpg/476px-Miss_constable_1787.jpg" border="0">

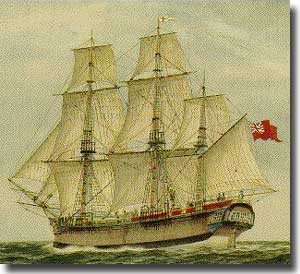

The Charlotte. Image courtesy of The First Fleet Home Pag

![]()

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_South_Wales_Corps

A marine private in 1788 and a private in the N.S.W. Corps received only

sixpence a day. whereas an officer received from twenty to fifty times more.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_South_Wales_Corps

A marine private in 1788 and a private in the N.S.W. Corps received only

sixpence a day. whereas an officer received from twenty to fifty times more.

I say, chaps we would have a better chance of hitting something, if they

had given us the ends of our muskets.

I say, chaps we would have a better chance of hitting something, if they

had given us the ends of our muskets.

Gov Bligh is arrested

.http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/gateways/archive/31/31.html

National Library Australia.

Gov Bligh is arrested

.http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/gateways/archive/31/31.html

National Library Australia.

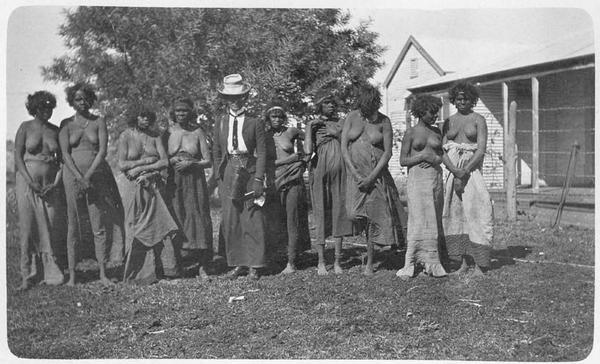

Convict and early pioneer photos.

http://www.bairdnet.com/pioneers/pioneers.html

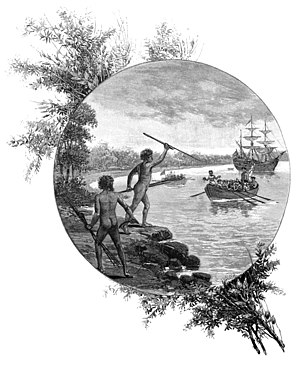

"The Native peoples are treated with respect and dignity." Report to the Admiralty.

Note the chains around the neck and manacles.

.http://www.militarybadges.info/brits/eras/02-nsw-corps.htm

N.S.W. Corps.

Governor William Bligh

The military force stationed in NSW from 1792-1810 was a specially raised unit, the NSW

Corps. They were nicknamed the 'Rum Corps' because of their monopoly in

trading in spirits. From 1806, the Governor of NSW was Captain (later Admiral)

William Bligh. Bligh, a talented and strong naval officer, has been somewhat villified

as an excessive disciplinarian in the accounts of the mutiny that took place on his ship,

HMS Bounty, in 1789. He recognised that the officers, in particular, of the NSW "Rum"

Corps were an entrenched power acting in their own interests. In particular, Bligh saw

that the small, non-military farmers were being disriminated against by the Corps.

As Bligh attempted to assert his legitimate authority, the Corps officers clashed with

the Governor over several issues including his support of small settlers and tensions

grew. On January 26, 1808, the troops, led by Lt-Col. George Johnston, arrested Bligh

and took over control of the Colony. A number of Bligh supporters were arrested, some

spending the next two years in convict work gangs.

This was Australia's only military coup. The NSW Corps remained in control

until 1810 when the British government sent a new Governor (Macquarie)

with his own regiment, disbanding the NSW Corps

Convict and early pioneer photos.

http://www.bairdnet.com/pioneers/pioneers.html

"The Native peoples are treated with respect and dignity." Report to the Admiralty.

Note the chains around the neck and manacles.

.http://www.militarybadges.info/brits/eras/02-nsw-corps.htm

N.S.W. Corps.

Governor William Bligh

The military force stationed in NSW from 1792-1810 was a specially raised unit, the NSW

Corps. They were nicknamed the 'Rum Corps' because of their monopoly in

trading in spirits. From 1806, the Governor of NSW was Captain (later Admiral)

William Bligh. Bligh, a talented and strong naval officer, has been somewhat villified

as an excessive disciplinarian in the accounts of the mutiny that took place on his ship,

HMS Bounty, in 1789. He recognised that the officers, in particular, of the NSW "Rum"

Corps were an entrenched power acting in their own interests. In particular, Bligh saw

that the small, non-military farmers were being disriminated against by the Corps.

As Bligh attempted to assert his legitimate authority, the Corps officers clashed with

the Governor over several issues including his support of small settlers and tensions

grew. On January 26, 1808, the troops, led by Lt-Col. George Johnston, arrested Bligh

and took over control of the Colony. A number of Bligh supporters were arrested, some

spending the next two years in convict work gangs.

This was Australia's only military coup. The NSW Corps remained in control

until 1810 when the British government sent a new Governor (Macquarie)

with his own regiment, disbanding the NSW Corps

During its service, the New South Wales Corps was criticised for the trading activities of some of its officers and their constant quarrels with a succession of naval governors, culminating in the deposing of the Governor, Captain William Bligh RN in 1808. Its military efficiency was such, however, that during the 1804 Castle Hill rebellion involving over 300 escaped convicts and others, a company of the Corps marched from Sydney to Parramatta in about three hours and, after a short rest, spent the remainder of the day subduing the convicts.

Who were the convicts?

Convicts building a road over the Blue Mountains, NSW, 1833. Charles Rodius 1802-1860. Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

While the vast majority of the convicts to Australia were English (70%), Irish (24%) or Scottish (5%), the convict population had a multicultural flavour. Some convicts had been sent from various British outposts such as India and Canada. There were also Maoris from New Zealand, Chinese from Hong Kong and slaves from the Caribbean.

A large number of soldiers were transported for crimes such as mutiny, desertion and insubordination. Australia's first bushranger - John Caesar - sentenced at Maidstone, Kent in 1785 was born in the West Indies.

Most of the convicts were thieves who had been convicted in the great cities of England. Only those sentenced in Ireland were likely to have been convicted of rural crimes. Transportation was an integral part of the English and Irish systems of punishment. It was a way to deal with increased poverty and the severity of the sentences for larceny. Simple larceny, or robbery, could mean transportation for seven years. Compound larceny - stealing goods worth more than a shilling (about $50 in today's money) - meant death by hanging.

Men had usually been before the courts a few times before being transported, whereas women were more likely to be transported for a first offence. The great majority of convicts were working men and women with a range of skills.

Good behaviour and 'Ticket of leave' licences

Good behaviour meant that convicts rarely served their full term and could qualify for a Ticket of Leave, Certificate of Freedom, Conditional Pardon or even an Absolute Pardon. This allowed convicts to earn their freedom (with restrictions). |

Convict Australia: Convict Life | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Convict Life A convict's life was neither easy nor pleasant. The work was hard, accommodation rough and ready and the food none too palatable. Nevertheless the sense of community offered small comforts when convicts met up with their mates from the hulks back home, or others who had been transported on the same ship. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

It's an historical episode that Australians don’t talk about much – after all, cannibalism by one’s ancestors is not the stuff of dinner party conversation. But now the story of Alexander Pearce, an Irish convict who ate his comrades while on the run, is being retold in a new film that has stirred debate in both Australia and Ireland.

The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce, made in Australia and starring two Northern Irish actors, opened in Tasmania recently and was shown on Ireland’s RTE Television on Monday. The film’s rather chilling tagline is: “No man knows what hunger will make him do.”

Pearce, a farm labourer, was transported to Australia in 1819 for stealing six pairs of shoes, and ended up on Sarah Island, a notoriously harsh penal colony off the west coast of Tasmania. Flogged repeatedly for the slightest misdemeanour, tortured and brutalised, he decided to escape, along with seven fellow prisoners.

Hacking through dense wilderness previously unpenetrated by white men, pursued by their jailors, and with little food to sustain them, the fugitives quickly grew desperate. They made their awful decision, targeting first Alexander Dalton. Robert Greenhill, a former sailor, cut Dalton’s throat, then Matthew Travers, a former butcher, decapitated him. All but two of the men consumed his flesh.

And so it went on, for seven weeks, until only Pearce and Greenhill were left alive. With Greenhill exhausted, Pearce killed and ate him. Finally recaptured, he confessed all to the British authorities, who refused to believe him. Surely no European would commit such horrific crimes?

Pearce was sent back to Sarah Island, but soon escaped again, together with an English convict, Thomas Cox. When caught, Pearce was lying beside the remains of Cox. This time, the evidence was irrefutable.

Pearce, who is played by Ciaran McMenamin, was convicted of murder and hanged in 1824. Before he died, though, he made a detailed confession to an Irish Catholic priest. Father Philip Conolly (played by Adrian Dunbar), who had been sent out to minister to the Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) penal colony, visited Pearce, chained to a wall in Hobart Jail.

The film, which will also be shown on British television, presents a surprisingly sympathetic picture of Pearce. Its Irish-Australian writer, Nial Fulton, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that, while he did not condone cannibalism, “I can empathise with the men that were on Sarah Island, I can empathise with the notion of doing anything to escape that kind of horror.”

Pearce himself used the phrase “No man knows what hunger will make him do”, and, according to Fulton, that question underlies the whole story. He said: “Unless you’re in that situation, and you’ve suffered the barbarity of what Pearce suffered, then you can’t begin to fathom what he went through.”

After he was executed, Pearce’s body was dissected for science, and his skull is still kept in the Museum of Pennsylvania.

The film’s director, Michael James Rowland, acknowledged that the episode was one of Australia’s founding stories, telling the ABC that “these very gothic tales often are at the root of Australia”. However, the nation had not turned out too badly, he added.

"Drunkenness was a prevailing vice. Even children were to be seen in the streets intoxicated. On Sundays, men and women might be observed standing round the public-house doors, waiting for the expiration of the hours of public worship in order to continue their carousing. As for the condition of the prison population, that, indeed, is indescribable. Notwithstanding the sever punishment for sly grog selling, it was carried on to a large extent. Men and women were found intoxicated together, and a bottle of brandy was considered to be cheaply bought for 20 lashes... All that the vilest and most bestial of human creatures could invent and practise, was in this unhappy country invented and practised without restraint and without shame"

– Marcus Clarke - For the Term of His Natural Life, 1867

" border="0" height="11" hspace="5" width="5">

" border="0" height="11" hspace="5" width="5">

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)

2 comments:

Post a Comment