I guess it was in the late fifties. So here I was in Melbourne and the people spoke a bit funny almost like my mum who came from Tasmania and my nana who said ”chimbley” for “chimney.”

They didn’t like much anything about Sydney, so I soon learned not to say I was from there. I tried not to say “eh” or “well” too much because that was a dead giveaway and the names for beer glasses were different too. Was it pots or middies or schooners or ladies waists that I asked for at the Exhibition hotel? “You must be from Sydney, fella. Don’t tell us about our marvelous sewage system the Yarra or I’ll dong yer one.” Said mine-host in a warning way.

I do recall meeting a blustery coot well into politics and booze. Also very opinionated (one knows another) at a pub down near the fruit and vegetable market. His mates called him Hawkie or Bob. I thought he was a bloody bore and told him so. He was also a drunk. I saw him cry one time when he was maudlin with liquor..

Years later the whole population of the Oz saw him cry on T.V. “You don’t know a bloody thing about politics”, said I,” (mister know- it- all,) after my fourth beer. “You’ll be in the gutter before you’re forty. Luckily he was too drunk to punch straight and I got hustled out of the pub by the burlies and deposited in a heap in a urine- smelling lane. Could that bloke ever lead the country? Well he had his chance.

I had a room in Carlton which, before the Greek influx, still tolerated the Aussie language and was certainly not upscale. They were proud of their football team. When I saw a game at a local oval, I couldn’t recognize it. So many players were jumping up to catch the ball and running the wrong way and not packing each other in scrums, where you could kick the other bugger’s ankles and hopefully make him lame.

“That’s a funny kind of Rugger,”I mentioned to a fellow onlooker “Is it League or Union?”

Wadder ya mean Rugger? That’s what the poofters up in Sydney play. We play the real fair dinkum game. “Aussie Rules.” The best bloody game in the world, mate.

My room in Carlton had a bed with inhabitants besides myself that came out of the cracks in the walls and settled in for the night with me.

There was a lowboy cupboard, a haven for moths and mosquitoes, where I hesitated to hang my two shirts, two strides and three pairs of socks, two with holes in the toes.

There was a kitchen down the hall with a greasy two gas burner which seemed to be leaking by the cloying gassy smell, a toilet for the stand-ups and another marked “ladies” for the sit-downs.

A more serious job had to be undertaken in an outhouse down the back which had a broken light-switch, and that meant you were in the dark after six. A sign said “No reading. Others may be waiting.”

When you went down the path past the choko vine, you had to ask “Anybody there?” and a double grunt told you if there was.

Another sign said “ Please conserve paper. Money doesn’t grow on trees.,”

“ No” I mused “but paper does, but there’s none in this lava-tree”. Luckily I had a sheet of the Melbourne Argus with me, which I couldn’t read in the dim light, but was useful anyway.

The shared bathroom had a grey-ringed bathtub with little curling hairs from someone’s crotch and the general cruddy greasiness from one lazy user to the next

.I found a piece of soap behind the tub, overlooked by the stingy management and I used an extra shirt to dry myself. I was not one for unnecessary towels which cost money to buy and were extra weight in my travels.

I took a shower which meant packing in paper and pieces of cardboard and whatever sticks you could find around the back yard into a burner under the shower. This roared away when you lit it and caused too hot water to spurt like a geyser when you started the shower but was too cold, as you finished. There was no shower curtain nor any mop, so shivering in the Melbourne chill, I just left the water spill over.

This brought the landlady to my door. “Mr Williams, please go back and wipe the bathroom floor. You’ve made a big mess. And there’s a paling from the back fence missing.” (I had broken it up for the water heater.)

“O.K. Mrs Reilly, but where do I get a mop?”

“If you won’t buy your own, you’ll probably find one in the back dunny.”

I went there and I heard two grunts.

“Excuse me mate, did you see a mop in there.? “

“Can’t see a thing. Black as the black hole of Calcutta. Sorry.”

“Yes, I know. I s’pose I’ll just wait for you.”

I’ll be here some time. I’m just starting me second smoke.”

I decided to go out to eat. All I had in my room was a peanut butter and jam sandwich tied in a paper bag hanging from a string . (to thwart the cockroaches.) I found a greasy spoon, the Acropolis Cafe a couple of blocks away. “Pies peas and potatoes, Dayg.” I ordered from the Greek.

“ How you know my name Dayg,” he asked me? My name Comino”.

“Oh, sorry sport, I left off the O at the end.”

Apparently he did not get the joke. He had a puzzled look on his Mediterranean dial.

I ate my meal” How much izzit, Dayg?”

“Four shillings and don’t come here no more.” He says.” I daon’a need customers like you galoots.”

“What was wrong with that Dago?” I wondered, going out. “I didn’t do nothing wrong.”

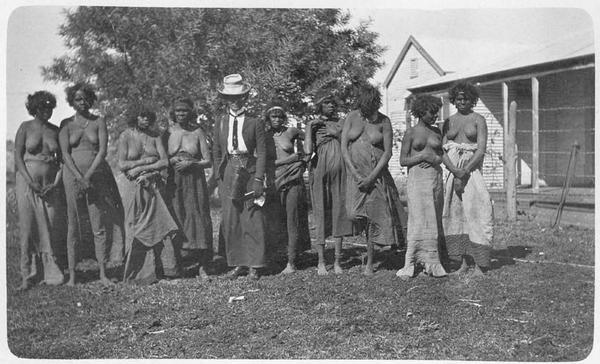

Such were conditions and attitudes among the Aussie working class in those days Aussies hated foreigners. There were laws against non-white immigration. Most people thought it was stretching it a bit to include Italians and Greeks among the whites. I just had the usual prejudices and was as ignorant as anybody.

Come to think of it, I wasn’t working class. I didn’t have a job at all. Counting my finances with the two bobs, pennies and three-pences and the odd ten shilling or quid note or two came to fifteen pounds, six and four pence. I had better start looking the next day.

I got up early, foregoing a burnt sausage and soggy toast breakfast with over-stewed tea (I pound a week extra) in the communal kitchen. I wolfed down another Melbourne meat pie which wasn’t a patch on a Sargeant meat pie with Fountain brand tomato sauce smeared under the crust. Good Sydney fare.. But it had to do, until I could find a fish and chip stand. I drank a banana milkshake

Later when I ordered fish and chips, I found I had been given a couple of pieces of school shark, which the uncivilized Melbournites actually ate .What about the flathead or whiting we were served in Sydney? Well I was a long way from home, seemed like.

They had trams, but you couldn’t scale them the way we did in Sydney. The off- side was blocked off so you had to climb up the correct way and as soon as you sat down a ticket collector would rush along to get your fare. Not like in Sydney town, where you had a sporting chance to avoid a sixpenny fare by jumping off and getting the next tram.

One thing about Melbournites in those days. They were a chummy mob, especially around Carlton.

Back home you could live next to someone for twenty years and hardly know the name with no more conversation than an occasional “Is the garbage collection on Tuesday or Thursday this week?

“ Tuesday I think, but it might be Wednesday. Depends how they feel about coming” “Yeah”.

I was in conversation with a fellow tram passenger in a few minutes.

“Where ya goin, to work?”

“No mate, I’m looking for a job. Know of any?”

“Well there’s work down on the wharves, if you can get in the union.. And you can get into the union if you’re a commo. Are you a commo?”

“ Don’t think so. I wouldn’t pass.”

“ Just go down to the union offices and talk about the ruling class and the workers don’t have a chance and old Jo is OK".

“Well I don’t know.” I was undecided. My fellow traveler got off the tram at the next stop. Flinders Street Station.

“:Heh!” he yelled “I heard they want men at the Zoo.”

“ Are you serious?” I called back as the tram lurched off.

“ Just go to Royal Park Zoo.” he laughed.” They’ll take you.”

Not knowing whether the bloke was rigey dige, I decided to try it. I’d never visited the Zoo here.

Taronga Park on the other hand, north of Sydney Harbour was one of my favourite places. I used to sneak in at the south- west corner, where the barbed wire was bent over and you could throw a piece of cardboard on it.

Me and Micky Finnigan hardly ever got hooked up, though his brother did one time and he started crying till we got him loose. The crying startled the animals and they made a real racket. Later when we were moving around making faces at the monkeys, a worker glared suspiciously, but he couldn’t have proven we didn’t come in the main gate

. He was most interested in young Finnigan’s scratched leg which was still bleeding, though I tied a hankie around it. “Where did that boy get hurt” he demanded.

“A lion jumped over the moat and bit him, sir.” said the elder Finnigan who was a bit of a wag. The worker went off mumbling “bloody kids.”

At the zoo entrance at Royal Park there were turnstiles. “Do you require a token?” said a feminine voice from behind a glass booth.

“ No, I just want to see someone about a job”.

“Well then, go through and along to your right. I’ll let you in.”

I decided to see a bit of the zoo first because I might not get the job anyway. I walked around for a half hour or so and just got to the great apes, when a security guard took my arm firmly “So you found a way to get in free, eh? Too bad you won’t be staying long.” He frog-marched me towards the exit.

“Hold it sport, I’m looking for a job and I was just examining how you treat the animals here, so I can get clued in, like.” Just then we were passing the administration block and unsure, he relaxed his grip and I went in.

After a wait, I saw someone in authority. He said he was the director. “What kind of work have you been doing?”

“Well,” my mind was working overtime to think up a good yarn “Well, my family had Alsatian Kennels and I did a lot of work for them. Then I worked for the N.S.W. National Parks at Kangaroo Valley.” (that sounded good)

“What did you do there?” He seemed to be accepting my story.

“Well I looked after Joeys that had been abandoned by their mothers. Stuff like that.”

“Hmmm” he looked thoughtful. “I suppose these animals were in an enclosure?”

“Yeah, that’s right. Four enclosures and I was in charge of them.” I thought I should make the story sound a bit important . I might get more money here.

“Do you think you could handle eight enclosures?” He asked me carefully. “Do you think you could look after eight enclosures every day?”

“Sure, why not,” I boasted “that’s nothing for someone with my experience.” I imagined telling my fellow tenants in Carlton how I was in charge of eight lots of animals.

It was pretty smart of me coming down to Melbourne. The people here were not as sharp as us Sydneyites, the way this gallah was lapping up my story. The closest I’d been to kangaroos was taking a potshot at a wallaby near Streaky Rock Hill with a .22 and missed ( luckily.)

“So you have the job. Congratulations.” The official told me affably, shaking my hand. “Be here tomorrow at 5.45 a.m. at the front gate. The head keeper will meet you.”

“Er… isn’t that a bit early? I don’t usually get up until around eight.?”

“Well Mr Sid Williams, you will know from your previous experience that the day starts when the animals wake up, and here they wake up before dawn.”

“ Sure. You are right” I agreed a bit uncertainly. I wondered if the trams ran from Lygon Street Carlton that early. Maybe some of the all-night trams, like the ones that kept me awake after the pubs closed, as I lay itching in the bug-infested bed in my mossie and mothy room, where I think I saw a cockroach the night before.

“Oh, can I ask you a question” I added as the zoo official opened the door for me.

“Will I be feeding the animals?”

“No” came his guarded reply, “The feeding end of the animals will not be your concern .The other end and what comes out will be..”

"I don't recall you at the Trades Hall Hotel, Williams. If I had swung at you, I would have connected. ."

"I don't recall you at the Trades Hall Hotel, Williams. If I had swung at you, I would have connected. ."

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)