| Six billion tons seems to be a lot of extra carbon for the Earth to handle each year, particularly since a little bit of this gas seems to go a long way. But let's put this in perspective for a moment. Fungi, molds, bacteria, microbes, termites, worms, beetles and slugs produce about twenty times as much CO2 as we humans do, and have been doing so from time immemorial. The Earth has been able to cope with that amount just fine. There is, in fact, a well-developed and immensely old mechanism in place to keep this gas in check. Is it reasonable to assume that the six billion extra tons of carbon will just accumulate in the atmosphere ad infinitum, until our race perishes in the ovens of a Bio-belzek? Or would it be logical to expect the rate of photosynthesis, and carbon burial, to increase and mitigate the effect? Recent observations would suggest the latter. Though the level of CO2 is unquestionably on the rise, it is not accumulating in the air quite as fast as we would otherwise expect. Some of the carbon is missing.

|

| The Gaia theory, first proposed by the British inventor James Lovelock in the 1970's, may help to explain the riddle of the missing carbon. It also explains a lot of the other peculiarities of planet Earth. The Gaia theory holds that the Earth's wildly improbable atmosphere, oceans and climate are constantly being regulated by the process of life itself, a single living organism which Lovelock called "Gaia" (from the goddess in Greek mythology). In the 1960's, NASA hired Lovelock to devise an experiment for detecting the past or present existence of life on Mars. His assignment forced him to consider the means by which one could detect the existence of life on Earth. As an atmospheric chemist, Lovelock, logically, first studied the Earth's atmosphere. Free oxygen, scientists agree, is the product of biological activity. Oxygen is also very reactive, and readily combines with other elements to form oxide compounds. Accordingly, it must be constantly replenished, or it will gradually disappear. Oxygen is also necessary for much of the life on this planet. Humans and virtually all other animals would quickly suffocate without it. About 21% of the Earth's atmosphere is comprised of oxygen. From the best information available to us, oxygen has remained at or near 21% for a considerable period of time. The mere presence of more than a trace of elemental oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere is evidence of the existence of life. The presence of a significant amount of oxygen on Mars would therefore be a signature of life (or at least life as we know it). But Lovelock became intrigued by a more basic question: how and why is oxygen, a highly reactive biologically produced element, held at a constant 21% in the Earth's atmosphere? The chance of this occurring randomly is virtually zero. Lovelock then observed another remarkable fact that further belied any notion that this could be mere coincidence: the figure of 21% is exactly the concentration of oxygen which is most conducive to the survival of life on the planet (at least, life as it currently exists). If the percentage of atmospheric oxygen was higher than this figure, much of the Earth's biomass would be combustible. If it was lower by even a few percentage points, most present animal life would suffer or even die.

|

| Lovelock also discusses other curious gasses in the Earth's atmosphere. These gasses include methane, ammonia and CO2, the first two of which are almost completely of biological origin. This gaseous triumvirate appears to have a crucial role in regulating oxygen, pH and surface temperature, respectively. Incredibly, the mixture and ratio of such gasses is precisely that which is needed to make the world most hospitable for life as we know it, and somehow these gasses have remained in this balance for an immense period of time. Lovelock summarizes these concerns:

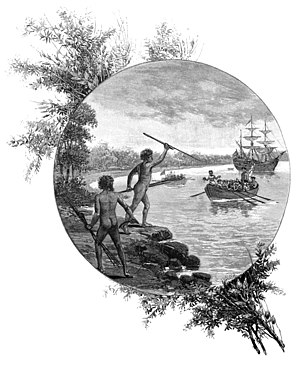

Life first appeared on the Earth about 3,500 million years ago. From that time until now, the presence of fossils shows that the Earth's climate has changed very little. Yet the output of heat from the sun, the surface properties of the Earth, and the composition of the atmosphere have almost certainly varied greatly over the same period. |

Lovelock Goes Nuclear

Gradually gaining wider acceptance in the scientific community over the past few decades, the fundamental principles propounded in the Gaia Hypothesis and subsequent work have been a catalyst for and instrumental to the work being done by the UN’s International Panel on Climate Change. Like many such powerful concepts, they grow beyond the ownership of those who originated them, however, and are often taken in many different directions, some of which run counter to or in direct opposition to the authors’ own views and intentions.

Lovelock, for instance, remains a staunch supporter of nuclear power, which I imagine makes him persona non grata to many environmental organizations, and leads to disparaging criticism as well as conveniently ignoring his views on the issue. I grew up in the cultural milieu Lovelock describes that produced in many, including myself, an elemental fear and dread of nuclear power—a combination of the Cold War threat of nuclear devastation and the anti-establishment youth culture that grew out of the civil rights and Vietnam War era in the US.

Now a good bit older and hopefully more prone to dispassionate reflection, I am more likely to consider and admit my ignorance on any of a variety of subjects and then seek out good sources of information to remedy this as opposed to the much simpler, more convenient and more often than not, emotionally driven option of forming a hasty and ill-formed opinion. Plus, I figure that the problems of environmental degradation and climate change associated with our fast-growing population and the development of modern consumer-driven societies is just too big and too substantial to merit anything less.

As I also cover mineral and energy resources for other online publications, I am aware of the meteoric rise in the market price of processed uranium ore, or yellowcake, over the past few years and the “nuclear renaissance” that some pundits say may soon come to pass. Feeling that it was my obligation as a journalist to recognize and transcend my own almost innate cultural biases and seek out the truth of the matter to the best of my ability, I felt that I needed to re-examine the ingrained, primarily emotionally driven beliefs that the risks of using nuclear power, and safely disposing of nuclear waste, are simply too great.

Unexpectedly, Gaia’s Revenge is helping me do just that. And I have to say that when it comes to nuclear power, which he considers our only safe bet when it comes to cutting back carbon dioxide emissions sufficiently to lessen the effects of the global “hot age” that he sees inexorably approaching, Lovelock has set me thinking.

Following are a few of what so far have struck me as among the most valuable and thought provoking quotes from Gaia’s Revenge regarding nuclear power, at least through page 133 of 204:

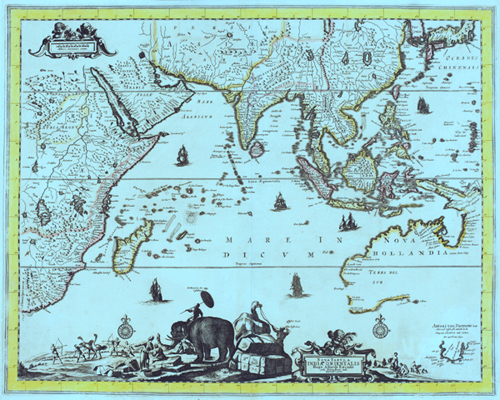

- A moment’s thought on the power densities of carbon fuels compared with nuclear fuels explains why the nuclear industry is small. To produce the same amount of electricity requires a million times more oil or gas than it does uranium. As a consequence, the nuclear industry can hardly afford pro-nuclear demonstrations and advertisements, and you rarely ever hear counter-arguments. - An outstanding advantage of nuclear over fossil fuel energy I show easy it is to deal with the waste it produces. Burning fossil fuels produces 27,000 million tons of carbon dioxide yearly, enough, as I mentioned earlier, to make, if solidified, a mountain nearly one mile high and with a base 12 miles in circumference. The same quantity of energy produced from nuclear fission reactions would generate two million times less waste, and it would occupy a 16-meter cube. - The carbon dioxide waste is invisible but so deadly that its emissions go unchecked it will kill nearly everyone. The nuclear waste buried in pits at the production sites is no threat to Gaia and dangerous only to those foolish enough to expose themselves to its radiation. - …I also knew that that the natural world would welcome nuclear waste as the perfect guardian against greedy developers, and whatever slight harm it might represent was a small price to pay. One of the striking things about places heavily contaminated by radioactive nuclides is the richness of their wildlife. This is true of the land around Chernobyl, the bomb test sites of the Pacific, and areas near the United States’ Savannah River nuclear weapons plant of the Second World War. Wild plants and animals do not perceive radiation as dangerous, and any slight reduction it may cause in their lifespans is far less a hazard than is the presence of people and their pets.

The fact that a scientist of Lovelock’s stature and staunch independence publicly offered to store the waste from one nuclear power plant on his own small plot of land in England certainly grabbed my attention and has given me food for thought and further consideration.

In Gaia’s Revenge, he states, “But it is not enough to use this as an argument favouring a wider use of nuclear energy, because the public belief in the harmfulness of nuclear power is too strong to break by direct argument. Instead, I have offered in public to accept all of the high-level waste produced in a year from a nuclear power station for deposit on my small plot of land; it would occupy a space about a cubic metre in size and fit safely in a concrete pit, and I would use the heat from its decaying radioactive elements to heat my home. It would be a waste not to use it. More important, it would be no danger to me, my family or the wildlife.

AP

A Przewalski's horse, one of several dozen of the primitive breed placed in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, being fed in a November 2000 file photo.

A

PARISHEV, Ukraine — Two decades after an explosion and fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant sent clouds of radioactive particles drifting over the fields near her home, Maria Urupa says the wilderness is encroaching.

Packs of wolves have eaten two of her dogs, the 73-year-old says, andwild boar trample through her cornfield. And she says fox, rabbits and snakes infest the meadows near her tumbledown cottage.

"I've seen a lot of wild animals here," says Urupa, one of about 300 mostly elderly residents who insist on living in Chernobyl's contaminated evacuation zone.

• ”

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

G

G

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment