Slideshow: Click an image to view the ships picture

Erotica in Art( not suitable for children)

Erotica in Art( not suitable for children)

Prostitution in the Convict Era "Wot a lass must do, to be well-to-do...""

In woman-short Port Jackson, the pickings are so good. Thus a girl must act "naturally"( as any smart one should.)

We sells our feminine feelings and brings you joy and lust.

Why not take a shilling or two, (as every smart girl must?)

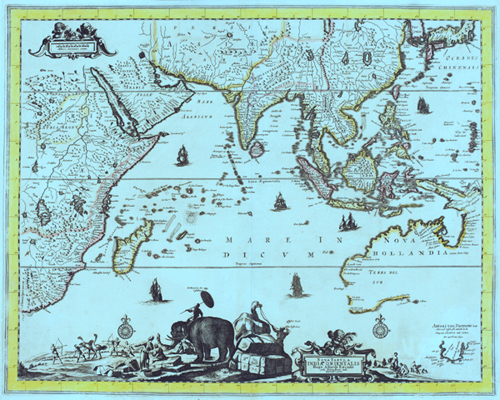

Historians are on firm ground when talking about prostitution in the post- First Fleet period, although our knowledge is by no means complete here either. As feminist historians have shown, prostitution was an integral part of the social and economic system of the early convict colonies. The numerical predominance of males on the first convict ships (amongst both convicts and gaolers) was from the outset perceived as a social and political problem: those in authority believed that 'without a sufficient proportion of that sex [female] it is well known that it would be impossible to preserve the settlement from gross irregularities and disorders' (Martin 1978, pp.22-9). Women were needed as an antidote to sexual deviance (read sodomy), rape of 'respectable' (read upper class) women, and rebellion. It was thus a matter of considerable urgency to find female sexual partners for the European colonists. Aboriginal women were obvious candidates for this role, and indeed Arthur Phillip, the first Governor, hoped that in time Aboriginal men would 'permit their Women to Marry and Live' with the convicts (Rutter, 1937). In the short term, however, this was not practicable and, as subsequent events were to show, liaisons between convict men and Aboriginal women were to cause much interracial tension (Reynolds, 1982). Having toyed with and rejected (on humanitarian grounds) the idea of luring Polynesian women to Sydney, the authorities turned to the possibility of bringing in significant numbers of women convicts. The issue here was not miscegenation, as it was to become by the end of the nineteenth century. Class considerations were paramount. The favourable response later on to Japanese prostitutes was based not just on their quietude but also on the fact that they didn't appear to have half-caste babies very roften.The plan was only partly successful. Only one quarter of the convicts transported on the First Fleet were women. If we add gaolers and officials to the numbers of males, women were outnumbered by roughly six to one in the convict settlements until the increase in free female immigration in the 1830s (Carmichael, 1992, p.103). To achieve even this level of comparability in the numbers of men and women, the authorities had to transport women on much less serious offences than those for which men were transported (Robson, 1963, 1965; Oxley 1988). But, the supply of female offenders was still not sufficient to keep pace with that of male convicts. This meant that, if the intention to use these women as sexual partners for convicts was to be fulfilled, some or all of the convict women would have to have multiple male partners. Indeed, in Phillip's opinion, 'the lusts of the men were so urgent as to require the prostitution of the most abandoned women to contain them' (Rutter, 1937). The fact that 12 percent of convict women were recorded as prostitutes before leaving Britain no doubt predisposed them to continue their former occupation in the colony (Robson, 1963). Other conditions in the penal settlements encouraged widespread prostitution. In the early years of the settlement no provision was made for housing for female convicts and a woman's best chance of accommodation was through striking up a liaison with some man. Those who could not or would not attach themselves to one man found the temporary bartering of sex for accommodation just as effective. Women were also the frequent targets of male violence and many found it necessary to seek the protection of one man, in return for sexual favours, against the sexual demands of other men. Limited opportunities for female employment in the early years, where the major demand was for male muscle-power, also placed pessure on women to prostitute themselves as one of the few ways in which they could earn a livelihood. According to Anne Summers, the result was a situation of 'enforced whoredom', either to one man or to many (Summers 1975, pp.267- 85; see also Alford, 1984, p.44; Aveling, 1992).

Prostitution in the Convict Era "Wot a lass must do, to be well-to-do...""

In woman-short Port Jackson, the pickings are so good. Thus a girl must act "naturally"( as any smart one should.)

We sells our feminine feelings and brings you joy and lust.

Why not take a shilling or two, (as every smart girl must?)

Historians are on firm ground when talking about prostitution in the post- First Fleet period, although our knowledge is by no means complete here either. As feminist historians have shown, prostitution was an integral part of the social and economic system of the early convict colonies. The numerical predominance of males on the first convict ships (amongst both convicts and gaolers) was from the outset perceived as a social and political problem: those in authority believed that 'without a sufficient proportion of that sex [female] it is well known that it would be impossible to preserve the settlement from gross irregularities and disorders' (Martin 1978, pp.22-9). Women were needed as an antidote to sexual deviance (read sodomy), rape of 'respectable' (read upper class) women, and rebellion. It was thus a matter of considerable urgency to find female sexual partners for the European colonists. Aboriginal women were obvious candidates for this role, and indeed Arthur Phillip, the first Governor, hoped that in time Aboriginal men would 'permit their Women to Marry and Live' with the convicts (Rutter, 1937). In the short term, however, this was not practicable and, as subsequent events were to show, liaisons between convict men and Aboriginal women were to cause much interracial tension (Reynolds, 1982). Having toyed with and rejected (on humanitarian grounds) the idea of luring Polynesian women to Sydney, the authorities turned to the possibility of bringing in significant numbers of women convicts. The issue here was not miscegenation, as it was to become by the end of the nineteenth century. Class considerations were paramount. The favourable response later on to Japanese prostitutes was based not just on their quietude but also on the fact that they didn't appear to have half-caste babies very roften.The plan was only partly successful. Only one quarter of the convicts transported on the First Fleet were women. If we add gaolers and officials to the numbers of males, women were outnumbered by roughly six to one in the convict settlements until the increase in free female immigration in the 1830s (Carmichael, 1992, p.103). To achieve even this level of comparability in the numbers of men and women, the authorities had to transport women on much less serious offences than those for which men were transported (Robson, 1963, 1965; Oxley 1988). But, the supply of female offenders was still not sufficient to keep pace with that of male convicts. This meant that, if the intention to use these women as sexual partners for convicts was to be fulfilled, some or all of the convict women would have to have multiple male partners. Indeed, in Phillip's opinion, 'the lusts of the men were so urgent as to require the prostitution of the most abandoned women to contain them' (Rutter, 1937). The fact that 12 percent of convict women were recorded as prostitutes before leaving Britain no doubt predisposed them to continue their former occupation in the colony (Robson, 1963). Other conditions in the penal settlements encouraged widespread prostitution. In the early years of the settlement no provision was made for housing for female convicts and a woman's best chance of accommodation was through striking up a liaison with some man. Those who could not or would not attach themselves to one man found the temporary bartering of sex for accommodation just as effective. Women were also the frequent targets of male violence and many found it necessary to seek the protection of one man, in return for sexual favours, against the sexual demands of other men. Limited opportunities for female employment in the early years, where the major demand was for male muscle-power, also placed pessure on women to prostitute themselves as one of the few ways in which they could earn a livelihood. According to Anne Summers, the result was a situation of 'enforced whoredom', either to one man or to many (Summers 1975, pp.267- 85; see also Alford, 1984, p.44; Aveling, 1992). There is considerable debate about the exact level of prostitution in convict society (Lake 1988). Historians such as Lloyd Robson (1965), Alan Shaw (1966) and more recently Robert Hughes (1987) have tended to accept the judgements of contemporary officials who condemned the female convicts generally as 'damned whores', possessed of neither 'Virtue nor Honesty'. But the evidence upon which this judgement is based is problematic. How can we know, for instance, whether the frequent allegations of universal whoredom reflected the class- and sex-based prejudices and preconceptions of literate officials more than actual practices in the colony? As Michael Sturma has pointed out, middle and upper class commentators tended to see working class women as prostitutes simply because their behaviour transgressed their own class-based notions of feminine modesty and morality. For instance, long-term de facto relationships were a common and accepted part of early nineteenth century working class culture, but from the perspective of the middle or upper class observer, these women were prostituting themselves, albeit to 'one man only' (Sturma 1978). Such men were also shocked by working class women's open and aggressive sexuality compared to that of 'virtuous' women of their own class (Daniels 1993). Early feminist historians such as Anne Summers and Miriam Dixson have ironically reinforced this picture of wholesale whoredom by incorporating the stereotype as a key element in explaining Australian women's current low status in relation to Australian men. Women were compelled into prostitution by State policy and structural factors rather than their own personal 'vice' but they were, by these accounts, prostitutes nonetheless (Summers 1975; Dixson 1975). Portia Robinson (1985), writing in the mid-1980s, presents the opposite view of the women of Botany Bay as good wives, good mothers and good citizens. If they were prostitutes, she says, it was as a result of their criminal environment in Britain rather than conditions in Australia. On the contrary, Australia offered women the chance for redemption (Robinson, 1988, p.236).

In the final analysis, it is impossible to know exactly how many women engaged in commercial sex during the convict period. Despite this, prostitution obviously was a key institution in convict society, providing one of the few economic options for women who supplied a high level of demand for sexual services in a disproportionately male population (Alford 1984). There is a sense, too, in which the actual numbers of women working as prostitutes is irrelevant to an understanding of the place prostitution played in colonial society. What is more important is the fact that those in authority believed it to be widespread yet, apart from ritual expressions of disgust, showed a high degree of toleration for the practice. As noted earlier, this toleration reflected the official belief that prostitutes provided a necessary outlet for the powerful lusts of working class men. It was also accepted because the women who provided this service were, from the point of view of the ruling class, the 'other' - working class women with values and behaviour markedly different from those of women of their own class. The sharp contrast between the speech, dress and behaviour of convict women and the demeanour of middle and upper class women also helped mask the extent to which sexual services were exchanged for financial gain across social classes. Because of this, convict society, particularly in the earlier decades, was noticeably more tolerant of women of 'easy virtue' amongst its upper echelons than was contemporary British society or later colonial society.

Deborah Oxley (1988, p.87) makes another important point in identifying prostitution as a structural part of the capitalist patriarchy which characterised colonising society. Working class women's role in this society was primarily to reproduce the working class: future, past and present. An intrinsic part of this role was the provision of sexual services to men, through marriage, force or payment. Sex was commercialised and turned into a commodity.

The convict era was thus crucial in setting the pattern for the history of prostitution in Australia. It saw the establishment of the sex industry as an important part of the life experience and work options of women within colonising society; it was also during this period that the extent of prostitution came to be used as a gauge of the worth of colonial women and of the success of colonial society more generally. Prostitution assumed a rhetorical and symbolic significance quite apart from its importance as an avenue for women's economic survival.

Only one quarter of the convicts transported on the First Fleet were women. If we add gaolers and officials to the numbers of males, women were outnumbered by roughly six to one in the convict settlements until the increase in free female immigration in the 1830s (Carmichael, 1992, p.103). To achieve even this level of comparability in the numbers of men and women, the authorities had to transport women on much less serious offences than those for which men were transported (Robson, 1963, 1965; Oxley 1988). But, the supply of female offenders was still not sufficient to keep pace with that of male convicts. This meant that, if the intention to use these women as sexual partners for convicts was to be fulfilled, some or all of the convict women would have to have multiple male partners. Indeed, in Phillip's opinion, 'the lusts of the men were so urgent as to require the prostitution of the most abandoned women to contain them' (Rutter, 1937). The fact that 12 percent of convict women were recorded as prostitutes before leaving Britain no doubt predisposed them to continue their former occupation in the colony (Robson, 1963). Other conditions in the penal settlements encouraged widespread prostitution. In the early years of the settlement no provision was made for housing for female convicts and a woman's best chance of accommodation was through striking up a liaison with some man. Those who could not or would not attach themselves to one man found the temporary bartering of sex for accommodation just as effective. Women were also the frequent targets of male violence and many found it necessary to seek the protection of one man, in return for sexual favours, against the sexual demands of other men. Limited opportunities for female employment in the early years, where the major demand was for male muscle-power, also placed pessure on women to prostitute themselves as one of the few ways in which they could earn a livelihood. According to Anne Summers, the result was a situation of 'enforced whoredom', either to one man or to many (Summers 1975, pp.267- 85; see also Alford, 1984, p.44; Aveling, 1992).

Convict women in early Australia. Women made up 15% of the convict population. They are reported to have been low-class women, foul mouthed and with loose morals. Nevertheless they were told to dress in clothes from London and lined up for inspection so that the officers could take their pick of the prettiest. Until they were assigned work, women were taken to the Female Factories, where they performed menial tasks like making clothes or toiling over wash-tubs. It was also the place where women were sent as a punishment for misbehaving, if they were pregnant or had illegitimate children. Other punishments for women include an iron collar fastened round the neck, or having her head shaved as a mark of disgrace. Often these punishments were for moral misdemeanours, such as being 'found in the yard of an inn in an indecent posture for an immoral purpose', or 'misconduct in being in a brothel with her mistress' child'. As women were a scarcity in the colony, if they married they could be assigned to free settlers. Often, desperate men would go looking for a wife at the Female Factories. Other men mostly officers would look for women for immoral purposes. | ||

The women, however, were treated as whores. They arrived at the gangplank of their vessel, the Lady Penrhyn, almost naked and filthy, "in a situation that stamps them with infamy", according to the officer in command of the expedition, Captain Arthur Phillip.

He was appalled at their treatment by the magistrates who had sentenced them and the jailers who had held them. Whether he could guarantee them better lives at the end of their nine-month voyage was yet to be seen.

What they were about to embark on was the longest journey ever attempted by such a large group of people. Where they were going might as well have been the moon. Crewmen, let alone convicts, believed they would never see home or their loved ones again. "Oh my God," wrote one officer of Marines in his journal, "all my hopes are over of seeing my beloved wife and son."

As for the country they were going to, almost nothing was known except for the promise of Captain James Cook, its discoverer, that this 'New South Wales' as he chose to call it, was now British. But, to some observers of the hang 'em tendency, the thought that the felons might be better off than if they had languished in jail provoked bitter reproach. They were getting a new life, courtesy of the state, some argued. One balladeer wrote: They go to an island to take special charge Much warmer than Britain, and ten times as large. No customs-house duty, no freightage to pay, And tax-free they'll live when in Botany Bay.

Judging by the behaviour of some of the prisoners on that first voyage, the balladeer may have had a point. In truth, some of those on board acted in a way we associate with holidaying in Ibiza.

As they crossed into the tropics, and the hatches were taken off at night to let the prisoners breathe in some cool air, sex was rampant. The women prisoners were like stoats, according to the surgeon on one of the ships. They threw themselves at the sailors and Royal Marines in "promiscuous intercourse", he declared.

"Their desire to be with the men was so uncontrollable that neither shame - but, indeed, of this they had long lost sight - nor punishment could deter them."

Some were put in irons and others flogged, but the going-price for a quickie was just a tot of rum from a sailor's ration. Not surprisingly, the next problem for the captain was drunkenness among the same women.

The voyage rolled on seemingly endlessly with stops at Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town. The last leg was into the swells and troughs of almost uncharted waters of the Southern Seas.

The convicts were more crowded than ever because room had to be made for cows, horses, pigs and sheep for the future colony. Still the lechery continued. "There was never a more abandoned set of wretches collected in one place at any period than are now to be met within this ship," said the surgeon on the Lady Penrhyn.

Violent thunder squalls dumped tons of freezing water on the halfclothed convicts and dampened some of their ardour. The ladies fell on their knees praying.

And, finally, 252 days after leaving England they had made it to dry land as the ships anchored in Botany Bay. Forty-eight people had died - 40 of them convicts, five convicts' children. It was a tiny death rate compared with what they had achieved in that voyage.

"The sea had spared them," wrote Hughes. "Now they must survive on the unknown land."

It was a fortnight before enough tents and huts could be made ready and the female convicts could be disembarked. Sailors and women went mad with lust again.

That night a storm blew down the tents and rain lashed the camp. Male convicts pursued the women intent on raping them. Sailors from the ships, fuelled by rum, joined in.

"It is beyond my abilities to give a just description of the scene of debauchery and riot that ensued during the night," wrote the surgeon.

There was swearing, quarrelling, singing - "it was the first bush party in Australia," wrote Hughes, "and as the couples rutted between the rocks, their clothes slimy with red clay, the sexual history of colonial Australia may fairly said to have begun".

The next day the new governor harangued the convicts. He would stand no repetition of last night's orgy. Prisoners who tried to get into the women's tents would be shot. There was back-breaking work to do just to survive and if they did not work they would not eat, he told them.

The convicts had come to a hard country, as tough as any prison back home. They looked out on a territory that appeared fertile and lovely but was in fact arid. Beyond the landing grounds was bush, mile upon mile of it. There were Aborigines out there, too. Try to escape and they would spear you.

Even the Marine officers who ran the colony despaired. One wrote, that 'in the whole world there is not a worse country. All is so very barren and forbidding that it may with truth be said that here nature is reversed and is nearly worn out'. Surely, he added, the government would not think of sending any more people here.

But it did. The colony survived for its first year largely on rations it had brought with it, a diet of salt meat and leathery cakes baked on a shovel. Crops failed, illness struck down dozens of the convicts. But then supply ships arrived, and after that more convicts.

For some life was too harsh to continue. Dorothy Handland, now 84, who had endured so much already since her conviction back in England, hanged herself from a gum tree. She was Australia's first recorded suicide.

............................................................................................................................................................

People looked at things differently in the early nineteenth century.

*

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment