Back to the Future 1929

Inflation could cut its value to one loaf of bread. It has happened before to the German Mark in the 1920's.

Inflation could cut its value to one loaf of bread. It has happened before to the German Mark in the 1920's.

On Tuesday, the U.S. national debt topped $9 trillion for the first time in history, according to the U.S. Treasury Department's daily accounting of the national debt. Nine trillion dollars! The number is so staggeringly high that it exceeds our ability to comprehend it in monetary units.

Million, billion, trillion – in financial terms, for most of us, it means a lot of money, really a lot of money, but that is about as specific a picture as most ordinary people can grasp.

Let's put all these “illions” into perspective. A million seconds is roughly 12 days, whereas a billion seconds is approximately 32 years.

We understand dollars. And we understand time. So it would take 12 days to pay back a million dollars at a dollar a second. But if you started right now, you'd pay back a BILLION dollars, at a dollar a second, in the year 2039.

A trillion seconds is roughly 32 thousand years. At a dollar a second, you'd pay back a TRILLION dollars in the year 34007.

The U.S. debt stands at $9 trillion. If my calculator is working, then at a dollar a second, the U.S. could be debt- free in the year 290007.

The point of that little exercise was two-fold. The first was to clarify the sheer volume of the debt; the second was to demonstrate the possibility that anybody in government really believes we can ever pay it off.

Each U.S. citizen's share of the national debt works out, according to the National Debt clock, to $29,947.50. That means the average American family of five owes, collectively, $149,737.50.

It also means that unless the average American family of five has a net worth of at least $149,737,50 in assets excluding liabilities (they don't), America is already bankrupt.http://www.dollarcollapse.com/

The way the U.S. Administration is rapidly printing currency to pay the $ 700,000,000,000 (actually closer to one+ trillion) a million dollars might buy you a meal in the future.

The way the U.S. Administration is rapidly printing currency to pay the $ 700,000,000,000 (actually closer to one+ trillion) a million dollars might buy you a meal in the future.  Unemployed march in the Great Depression.http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rails/timeline/index.html

Unemployed march in the Great Depression.http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/rails/timeline/index.html Run on Banks.and people lost their money.

Run on Banks.and people lost their money.Poverty.. poor workhouse children, England-Australia.

Hell on earth: A scene of poverty in the slum area around St Giles's in the City of London

Most Londoners preferred to forget that it even existed. When Mowbray put on his boots and walked through the Old Nichol, he passed down narrow, muddy streets, skirting pools of filthy liquid and the carcasses of dogs and cats.

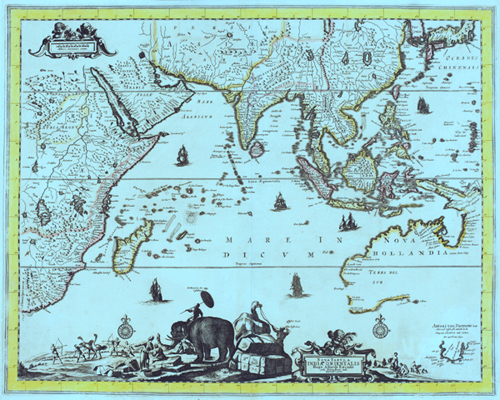

Convict Children."The children of transported convict women under sentences of confinement at the Parramatta Female Factory were taken from them when they reached the age of three and taken to the Government Orphan Schools. Here the children remained until the boys were apprenticed at 10 years of age; or the girls found domestic work or married".

A portion of the convicts sentenced to transportation to New South Wales were children, mainly boys who had been convicted of minor crimes like theft. One child was Mary Haydock, who at the age of 13 had been sentenced to seven years'transportation for merely possessing ahorse that was not her own. Thepunishment delt out to those guilty ofpetty crimeswere harsh.

The young female convicts of this time were assigned to settlers asservants or worked in Female Factories in Parramattaor Hobart. Some girls were lucky and were sent to serve kind families which regarded the female convict as a member of their own family. Others were lessfortunate and were sent to homes that saw them abusedandoverworked.

During the early 1830's, male convict children were sent toTasmania'sPort Peur, which was situated near the well known and notorious Port Arthuradult's prison. These boys were usually aged 9 to 18, and were considered to be too weak to work for settlers as they were suffering frommalnutrition.

The Boy's establishment at Point Peur was built by the young boys themself during 1834. Soon the amount of boys being sent to Point Peur increased and a daily routine was established for boys to follow. At 5am they were to awake and put away the hammocks they had slept on. Next, they would be supervised by overseerswhile they washed in tanks of cold water outside. The morning continued on withprayers, breakfastand anassembly. They would then proceed to classes atworkshopswhere they were taught a trade. An hour's play was given to them at midday, which was followed by lunch. Half the boys went to school while the other half worked on the prisonfarms from 2pm until 5:30pm. The boys had yet another hour's play untildinner at 6:30pm, and boys were read to before bed. Lights out was promptly at 9pm. Boys who misbehaved were placed in solitary confinement, chained or given 30 strokes of thelash. One of the most serious cases of child rebellion was of two 14-year-old boys murderingtheir disliked overseer by hurlingstones. Some boys attempted to escape Point Peur, although most were unsuccessful and drowned at sea

In 1788 with a cargo of 552 convict men and 190 convict women. This distorted ratio of male to female was to become a constant concern for the British GovernmenT Britain was anxious for the New South Wales civil society to develop along conventional lines. Despite their concerns, the population's liaisons were unconventional. The records suggest that authorities thought that homosexuality was commonplace amongst convict men and women.

- When large scale rebellions occurred amongst convicts, the army was used to restore order. These revolts were frequenT Groups of convict men and women attacked their keepers, stole ships, torched their gaols and 'bolted' to the bush. Aboriginal Australians were asked to help track down escapees. In the Port Phillip Bay colony, the army organised units of Aboriginal Australians into a uniformed "Black Police".

- The children of transported convict women under sentences of confinement at the Parramatta Female Factory were taken from them when they reached the age of three and taken to the Government Orphan Schools. Here the children remained until the boys were apprenticed at 10 years of age; or the girls found domestic work or married.

- The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay in 1788 with a cargo of 552 convict men and 190 convict women. This distorted ratio of male to female was to become a constant concern for the British GovernmenT Britain was anxious for the New South Wales civil society to develop along conventional lines. Despite their concerns, the population's liaisons were unconventional. The records suggest that authorities thought that homosexuality was commonplace amongst convict men and women.

- When large scale rebellions occurred amongst convicts, the army was used to restore order. These revolts were frequenT Groups of convict men and women attacked their keepers, stole ships, torched their gaols and 'bolted' to the bush. Aboriginal Australians were asked to help track down escapees. In the Port Phillip Bay colony, the army organised units of Aboriginal Australians into a uniformed "Black Police".

- The children of transported convict women under sentences of confinement at the Parramatta Female Factory were taken from them when they reached the age of three and taken to the Government Orphan Schools. Here the children remained until the boys were apprenticed at 10 years of age; or the girls found domestic work or married.

It was believed by societythat poor children should work. The most common form of employment for girls was working as adomestic servant for wealthier families. They began their day's workearly, before thehousehold had awoken, and continued working until night. Most girls started working as domestic servants from the age of 10 to 12. Other young females took upapprenticeships in thetextile industry, or worked in shops andlaundries.

Boys became apprenticed in one of a wide selection of trades at the age of 10. In most cases they went to live in the home of thecraftsperson to whom they were apprenticed. A craftsperson held theauthority to severelypunish an apprentice on the grounds of clumsiness,laziness, or anything else they thought suitable.

Children too young to serve apprenticeships or work as a servant helped look after horses, ranerrands and openedcarriage doors with the expectation of recieving atip. Some children as young as six wereemployed to complete minor tasks on farms. However, wealthy children were not expected to work -- instead they received an education. Many young children from 8 or 9, boys and girls roamed the streets and alleys of Sydneytown prostituting themselves for oral and anal sex for a few coins. There seems to have been no illegality in this and Governor Phillip remarks in his journal about this lamentable state of affairs. London in the 1780s was a rapidly burgeoning city of almost a million inhabitants, mainly proletarian. Over the previous three decades, England had been radically transformed from a nation of mainly rural dwellers, living and dying in the same hamlet, into an industrial workshop. Traditional family structures were broken up and landless labourers driven into towns and cities, where they were crowded into slums generally unfit for human habitation, entirely dependent for survival on daily wages. Life was precarious and regular work no guarantee of survival. According to one estimate, the average age of death among operatives (unskilled workers) at this time was 19 years.

John Hudson was an orphan, undoubtedly one of tens of thousands of unwanted infants abandoned by the poor and destitute. Most of these babies quickly perished. Others died more slowly from malnourishment, cold, exhaustion, neglect, cruelty or a range of diseases. Infants and children under five, overwhelmingly from the working-class, accounted for almost half of all the deaths in London during the mid-18th century.

Holden cites several contemporary observations about this social crisis. One written by Jonas Hanway in 1772 and entitled Observations on the Causes of Dissoluteness which Reigns among the Lower Classes of the People...Likewise a Plan for Preventing the Extraordinary Mortality of the Children of the Labouring Poor in London and Westminster refers to the low cash value of the children of the poor.

“Orphans... or the illegitimate children of the poorest kind of people,” according to Hanway, “are said to be sold; that is, their service for seven years is disposed of for twenty or thirty shillings; being a smaller price than the value of a terrier.”

Holden also cites Jonathan Swift's satiricalModest Proposal, written in 1729, to put the children of poor Irish to some use. “A young healthy Child... a year old, [is] a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome Food; whether Stewed, Roasted, or Boiled.” Other “advantages,” Swift writes, was that “men would become as fond of their wives during the Time of their Pregnancy as of their Mares in Foal... and it would prevent those voluntary Abortions, and that horrid Practice of Women murdering their Bastard Children".

Though written in reference to Ireland, Swift's Modest Proposal, Holden correctly observes, was “just as relevant 50 years later and for that generation of children who sailed on the First Fleet".

It is not known how Hudson survived for almost nine years before he came to official notice. Like most working class children, he was illiterate and kept no diary or written record of his life.

Holden quotes the Old Bailey Session Papers of 1783, where his brief interview with the judge at the time of his trial provide the first documented account of Hudson's existence and some indication of how he lived:

Court to Prisoner: “How old are you?”

“Going on nine.”

“What business was you bred up in?”

“None, sometimes a chimney sweeper.”

“Have you any father or mother?”

“Dead.”

“How long ago?”

“I do not know.”

Coffins of black

As a chimney-sweep, permanently blackened with layers of soot to provide some protection against the fire and heat of chimneys, Hudson was among the most visible of child labourers. But in many other respects his life was not much more wretched than that of his peers. Most children, less visible in mills, mines and foundries, commonly worked 12-hour days, many from an early age.

Many chimney-sweeps were recruited from the age of four. Small boys were needed with bones soft enough to crawl through the tiny chimney flues or “coffins of black” as the poet William Blake called them. Some chimney openings were as small as 9 x 14 inches (23 x 35 centimetres).

Holden provides a picture of the horrendous conditions facing chimney sweeps and the terrible toll it took on their health. “[E]mployed to scrape the soot from the sides of the flue, [the boys also had to] replace the mortar which had become dislodged and repair cracks in the brickwork. Oven chimneys were particularly unpleasant as deposits of congealed fat and soot made it difficult to get any firm grip. Constant lacerations were a permanent part of life. For some a relatively quick death by asphyxiation or by smoke inhalation may have been preferable to the long-term sufferings which were an occupational habit and which might have included asthma, inflammation of the eyes, burned limbs, malformed spines and legs and tuberculosis. Most horrifyingly, these young children often developed cancer of the scrotum.”

The most profitable aspect of the mastersweep's business was extinguishing flue fires. To do this the mastersweep would force the children to climb up the chimneys and extinguish the fires from the inside. “For this task, the boys entered the mouth of the chimney carrying a candle in their teeth and a scraper in their hands. They climbed by way of their knees and elbows to the top and then worked their way down.”

Indicating how much the children hated this work, Holden refers to a chimney-sweep in 1819, who gladly consented to the amputation of a leg crushed in a fall, after being told that he could not ascend another chimney with only one leg.

Hudson was a “sometimes” chimney-sweep because it was an itinerant occupation and their masters traditionally cast out apprentices during the warmer months, usually from May 1 on. The masters then set up as night-carters, a business that did not require small-limbed apprentices, and the boys left to roam the streets. The boys were also dispensed with as soon as they outgrew the narrow flues and chimneys.

Is it surprising that Hudson took to petty theft? Was there any other way to mitigate the wretched circumstances of his life? As Holden concludes, John Hudson in 1780s England was a “little black slave” with nothing to lose.

+copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment